The advance towards the Mediterranean Sea

The North African campaign and the Casablanca Conference.

The invasion of Europe began to be planned during the Casablanca Conference, January 1943. The meeting was attended by the Allied leaders to outline a plan in order to definitively defeat Hitler and Mussolini. The first stage that was considered determining was the Allies’ victory in North Africa.

The North African Campaign (1940-1943) saw the succession of bloody battles between the Allied front and the Axis. It ended in May 1943 with the final Allied victory.

National Archives and Records Administration 1942, North Africa, British activities in Tunisia

National Archives and Records Administration 1943 – Italian children in Ethiopia sent home by the British

Having defeated the Axis in Africa, the Allies could control way more easily the Mediterranean basin and even employ airbases for the bombings in Europe. As a further consequence, the German troops weakened the pressure on the Eastern front, because of the potential threat to the “Fortress Europe”, therefore facilitating the Soviet Red Army’s counterattack .

IWM North Africa 1943 No. 150 Squadron RAF

IWM North Africa, the crew of a Vickers Wellington Mark X of No. 150 Squadron RAF

Objective: attack on Italy

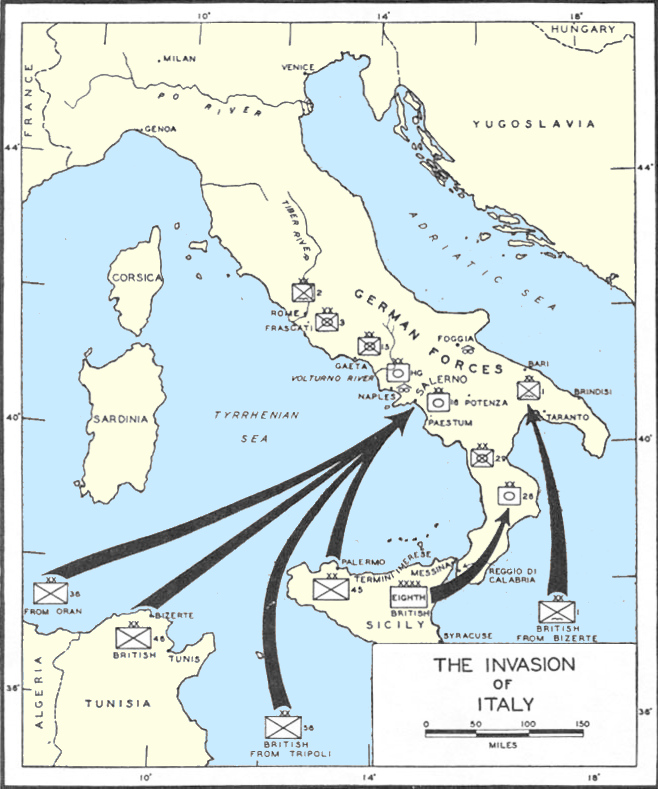

After a heated debate among the “big three” (Stalin, Roosevelt and Churchill) about where it would be preferable to open a front in Europe, the British idea of attacking Italy prevailed, as opposed to Stalin’s position, who would have preferred to open a front in France, so as to threaten Germany more directly.

The Italian campaign had the aim of hitting the “soft underbelly” of the Axis with a view to quickly attacking Germany from the South. Mussolini’s regime was deemed unstable and the national defence inadequate. However, the Allies underestimated the effectiveness of the German troops placed throughout the country, led by the general Albert Kesselring.

Radio London

Within the framework of the ventures that can be considered preparatory to the landing in Italy, Radio London broadcasts must be included. The Allies directly addressed the part of the population that resented the fascist regime and that, just by clandestinely listening to those broadcasts, could feed the flame of hope in an upcoming change.

Radio London began broadcasting in 1938. They were BBC broadcasts in different national languages that during the war were addressed to civilian populations but also to several national resistance groups with coded messages. In this way, on the one hand it predisposed local people to receive British troops in a welcoming way, whereas, on the other hand, it carried out an actual operating activity in support of the military action.

Exactly in 1943, when the axis of the war started shifting towards Europe, the British intensified the communication. Listening to Radio London was obviously a clandestine activity and it was harshly opposed and repressed by local regimes.

The tone and the contents aimed at building a trustful relationship with the Italians, as demonstrated by the closeness transpiring from the speech made by J. Haslip, on 8 September 1943:

“Now that Allied armies advance on Italian ground and that at any moment the humblest of the abodes can become a strategic point in the global battlefield…”.

In this publication by the State Archives the inventory of the broadcasts in Italy is available.

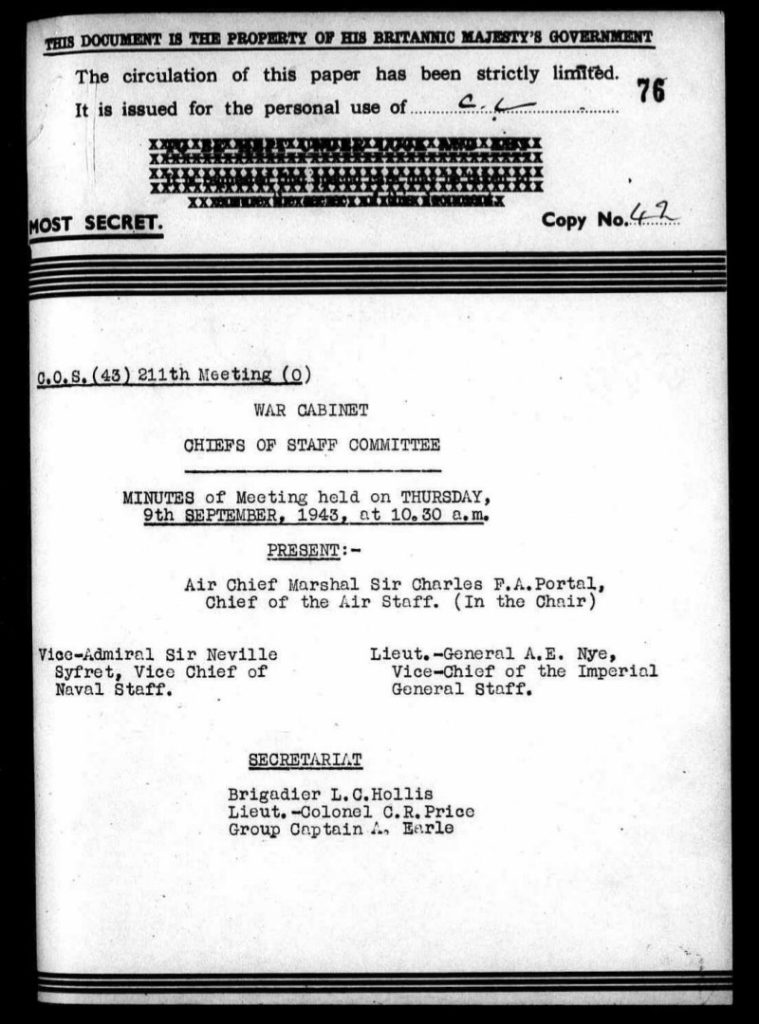

Preparatory studies: developing the “Avalanche” plans

The idea of landing in the area of Salerno took shape during a meeting in Tunisi, on 26 July 1943. Thus, the operation “Avalanche” was born. The delicate planning phase of the Allied strategy, in view of subsequent operations, intertwined with a phase of more and more intensive contacts between the Italian government and the Anglo-Americans, until the armistice was signed at the beginning of September 1943. In a number of military briefings, between the end of August and the middle of September 1943, the Allies discussed the need for additional forces for “Avalanche”, as evidence of the actual urgency acknowledged to the operation.

The protagonists: the British Eighth Army.

The US and the British army took part in the Italian campaign. The Eighth Army was a military task force that, from 1941, gathered the fighting forces of the Commonwealth deployed in the Middle East. It fought in the North African campaign and then it was employed in Italy from the landing in Sicily. Indeed, both in Africa and Europe, a significant part of the war effort was borne by the British.

Throughout the landing in Salerno, the British Army constituted the largest contingent and it was led by General Montgomery, who ascended, together with other corps, from Calabria, where he had landed over the course of operation Baytown.

The Eighth Army, as we shall better see later, was to be considered a multinational force proper, since it gathered, under the Union Jack, means and men coming from several nations of the Commonwealth and not only: with New Zealanders, Canadians, Indians and the British fought French, Belgian, Dutch, Polish soldiers and other men from different occupied countries.

Città di Battipaglia

Città di Battipaglia