From Naples to the Gothic Line

The Germans begin their retreat

Ten days after the landing, General Albert Kesselring’s German troops began their retreat and the Allies consolidated their positions on Salerno.

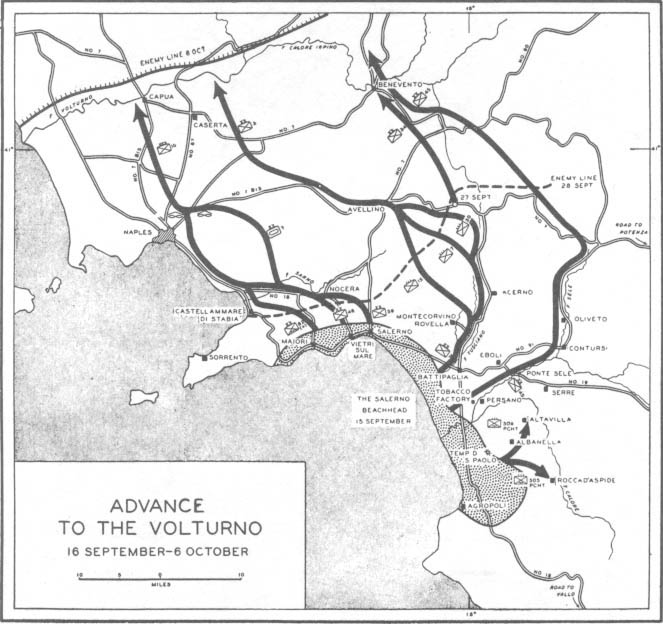

General Alexander, commander of the Allied forces, outlined the plan for the advance towards Naples: the US Fifth Army had to reach the city by crossing the Volturno on the western side of the Apennines while Montgomery’s British Eighth Army had to advance along the eastern side. However, the march towards Naples was anything but simple, both due to the adverse weather conditions and to Kesseling’s delaying tactics which slowed down the advance towards the administrative centre.

Many places offered the Germans the possibility of forcing the Allies into long and dangerous battles, which slowed down their advance: Molina di Vietri, Cava de Tirreni, Scafati…

The Allies enter Naples

1st October 1943

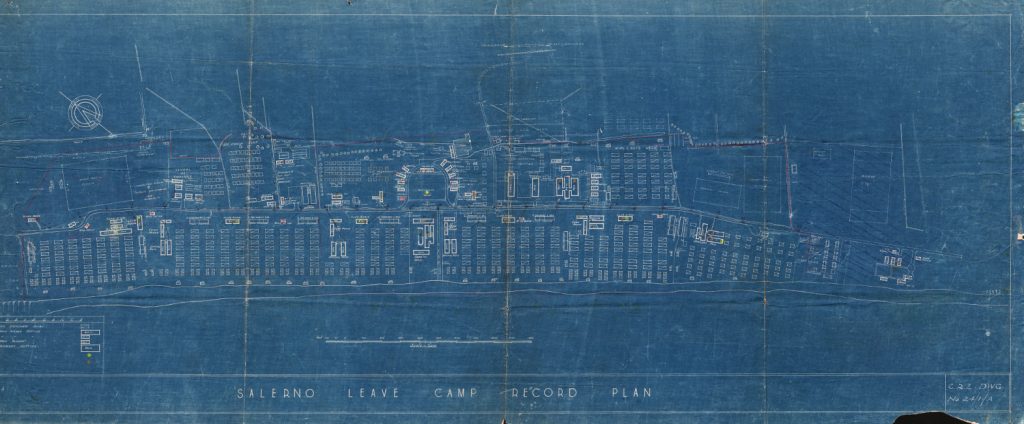

Operation Avalanche officially ended on 1st October 1943 with the arrival of General Clark’s Fifth Army in Naples, which had already been freed thanks to a popular uprising by its citizens during the “glorious” Four Days. The conquest of Naples, which was the largest port in Italy and the third most populous city of the peninsula at the time, represented the greatest success of the Allies until that moment in the entire Mediterranean campaign.

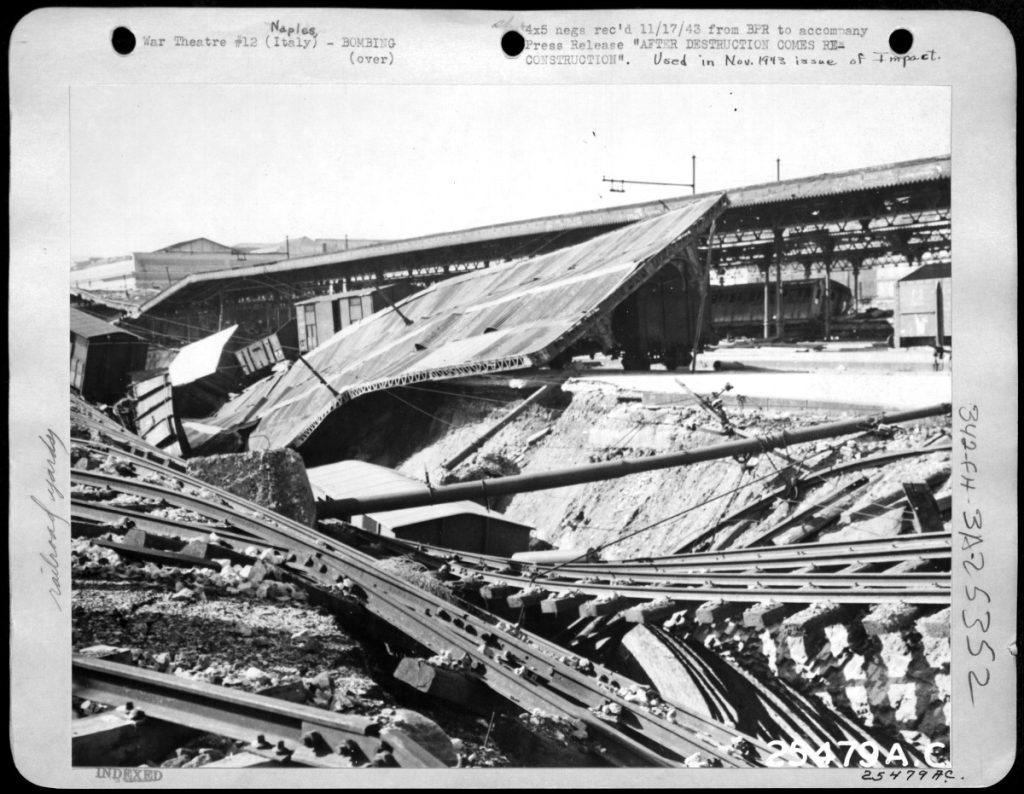

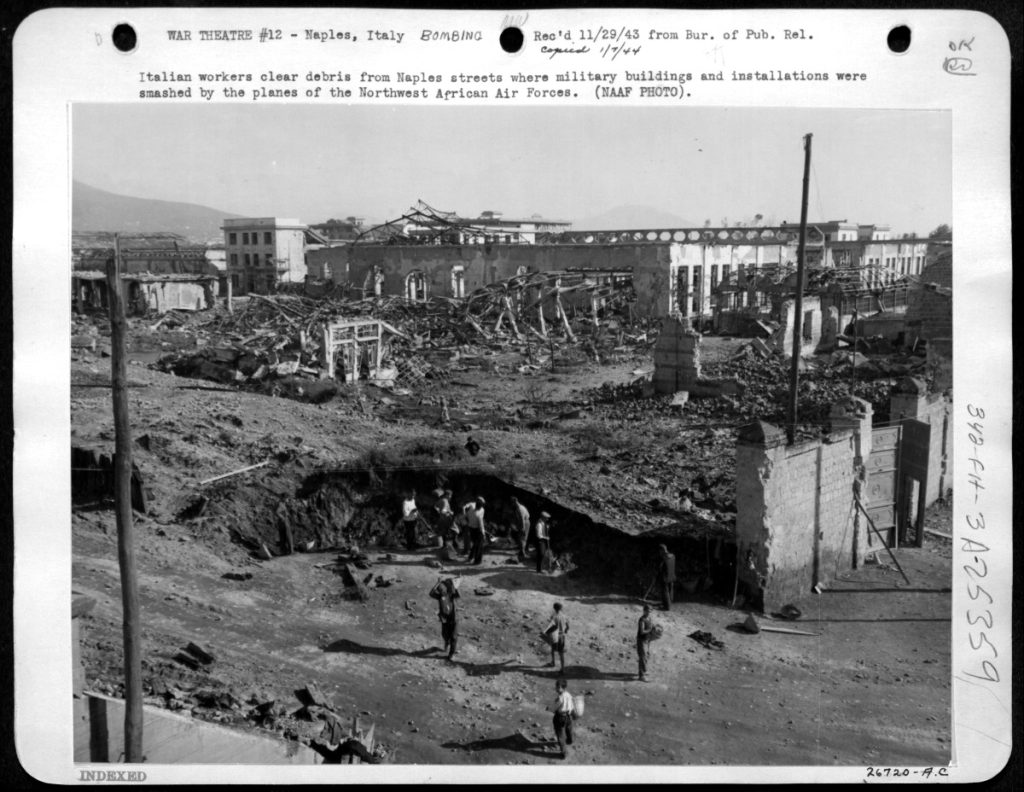

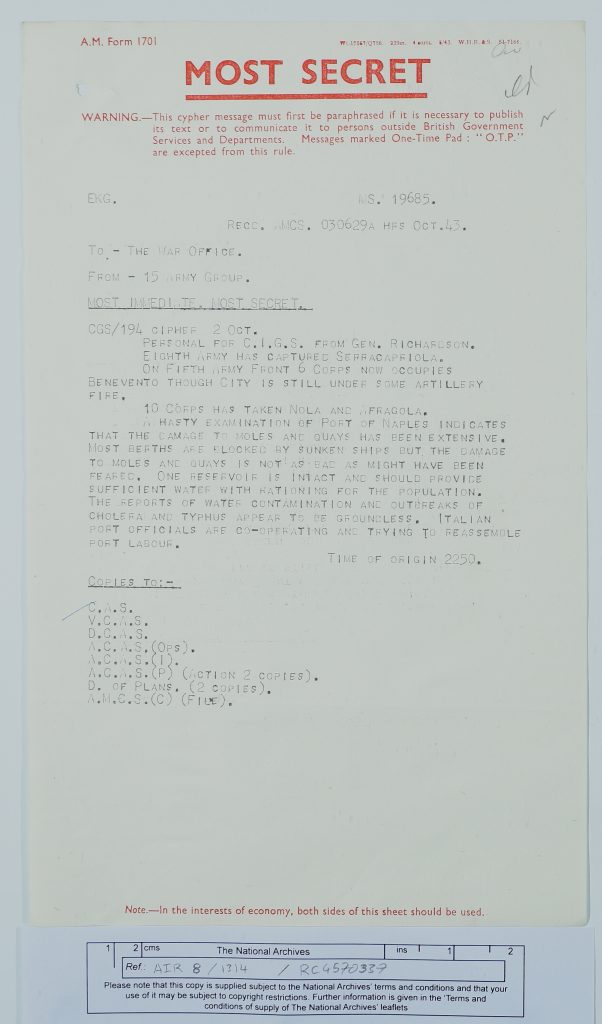

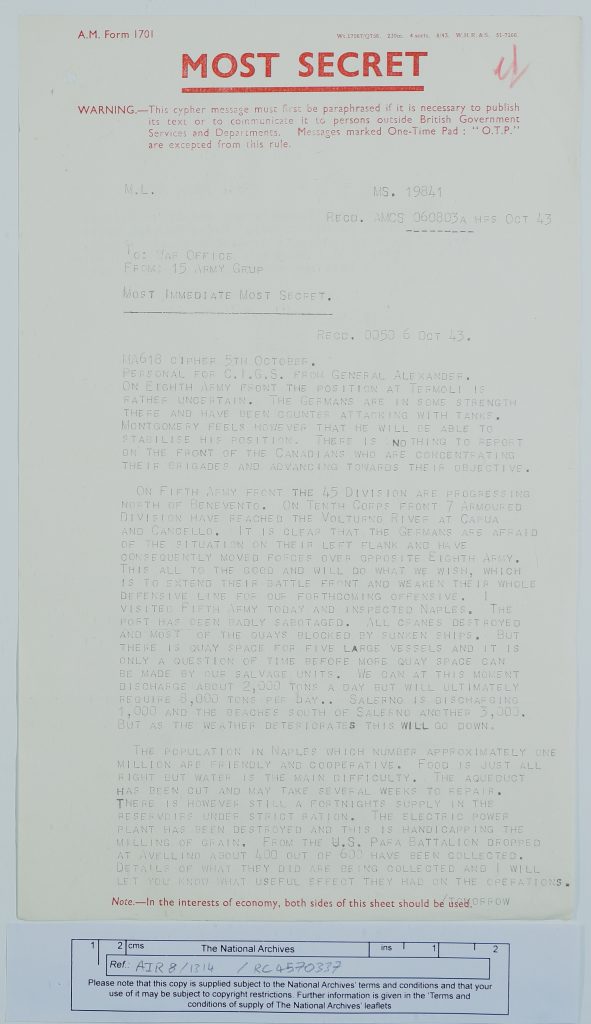

The experience of the Allied military occupation in Naples has become exemplary in order to understand the complex relationships established between the Allied and the locals. In his notes, General Alexander, head of the 15th Army Group, defined the Neapolitan population as «friendly and cooperative», while not neglecting to observe the rampant despair. Having personally gone to Naples for a quick inspection, he noticed that the city’s port had been sabotaged and destroyed, whilst the majority of the ships sunk.

In addition to food shortage, one of the most alarming problems was the supply of drinking water, since the city’s aqueduct had suffered extensive damage from the bombing and the tanks were depleting. Throughout the area, water contamination was the root cause of typhus and cholera epidemics.

“Zone handbooks” were also important, that is military guides on the several areas of Southern Italy and the Mediterranean, which were prepared as the Anglo-American armies moved up the peninsula. They were intended to provide officers and soldiers with all the necessary information on the liberated territories.

From the guide dedicated to Campania, dating back to August 1943, it is evident that in Naples, as in other cities in the South, the people who thronged the squares and alleys were the true soul of the city:

«Noisy and always active, light-hearted, but not happy. […] screaming men, yelling women, cackling children, sobbing babies, the street teeming with life in the midst of a disconcerting chaos, and in the midst of which the cries of peddlers of fish, fruit and vegetables continually creep [ …] the street is the true home of the Neapolitan […] where the human voice, hardly recognizable as such, dominates everything, even the countless bells.»

A lot of accounts left by the traveling allied soldiers are as well rich in such bright shades of color, even though these vivid descriptions sharply contrasted with the much sadder images of a city devastated by the war in body and soul, as the troops passed.

Naples had been hit hard by the Allies first and then likewise devastated by the Germans on the run. It was in a situation of tremendous poverty and its infrastructures were destroyed.

National Archives and Records Administration – Naples

Allison Collection: welcome to Resina

From Naples to the Gothic Line: Cassino, Anzio e Roma

The advance of the Allies from Naples to Rome lasted eight months. After the liberation of Naples, the allied troops were held back by the excellent defense organized by Kesselring on the famous “Gustav line” along the road between Naples and Rome.

Rome had already been occupied by the Germans in September, who had taken it away from Italian control despite the fact that the royal army was numerically far superior. The lack of orders from high commands, as a consequence of the king’s flight to Brindisi, prevented the organization of an adequate defense with the exception of some sporadic self-organized acts of resistance. The city became easy prey for the Nazi army and was formally declared an “Open City”.

Fundamental stages in order to overcome the German resistance were the landing at Anzio (January 1944) and the battle of Cassino (January-May 1944).

National Archive and Records Administration – The final attack in Montecassino, from the documentary The Liberation of Rome

The allies, blocked along the route to Rome at Cassino, tried to break the deadlock thanks to a pincer movement which consisted of a new landing (Operation Shingle) in the area of Anzio to outflank the German resistance. Only a few months later, however, the Allies broke through the front in Cassino, even at the cost of very heavy bombings.

On 4 June 1944 the Allies finally entered Rome.

National Archive and Records Administration – The entrance in Rome, from the documentary The Liberation of Rome

Città di Battipaglia

Città di Battipaglia