Propaganda: the illustrated war

The approval of totalitarian regimes has always been based on the projection of their own specifically constructed public image and on the repression of alternative sources of information. Germany and Italy, with their Ministry of Propaganda, headed by Goebbels, and the Ministry of Popular Culture, further specialize the manipulation of consensus. With the war, however, other countries as well deal with the conflict with their own specific structures dedicated to information, such as the US Army Signal Corps or the Crown Film Unit.

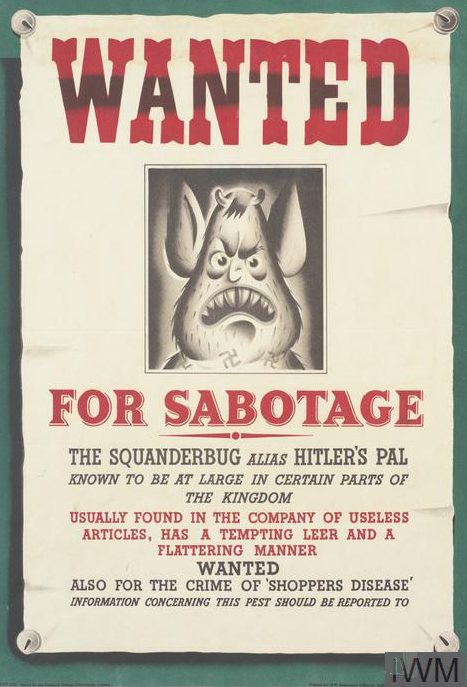

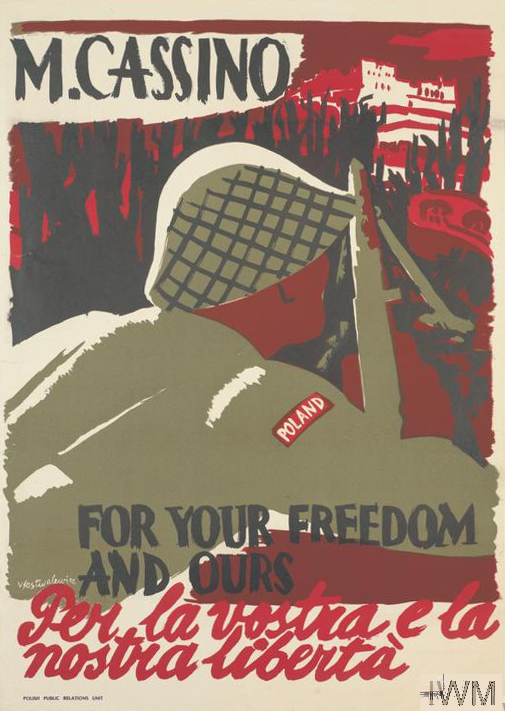

Propaganda posters

Musée du Général Leclerc de Hauteclocque et de la Libération de Paris, musée Jean Moulin, “It’s a long way to Rome. 1944.

IWM Wanted for Sabotage – anti-spy propaganda

IWM celebration of the Battle of Cassino

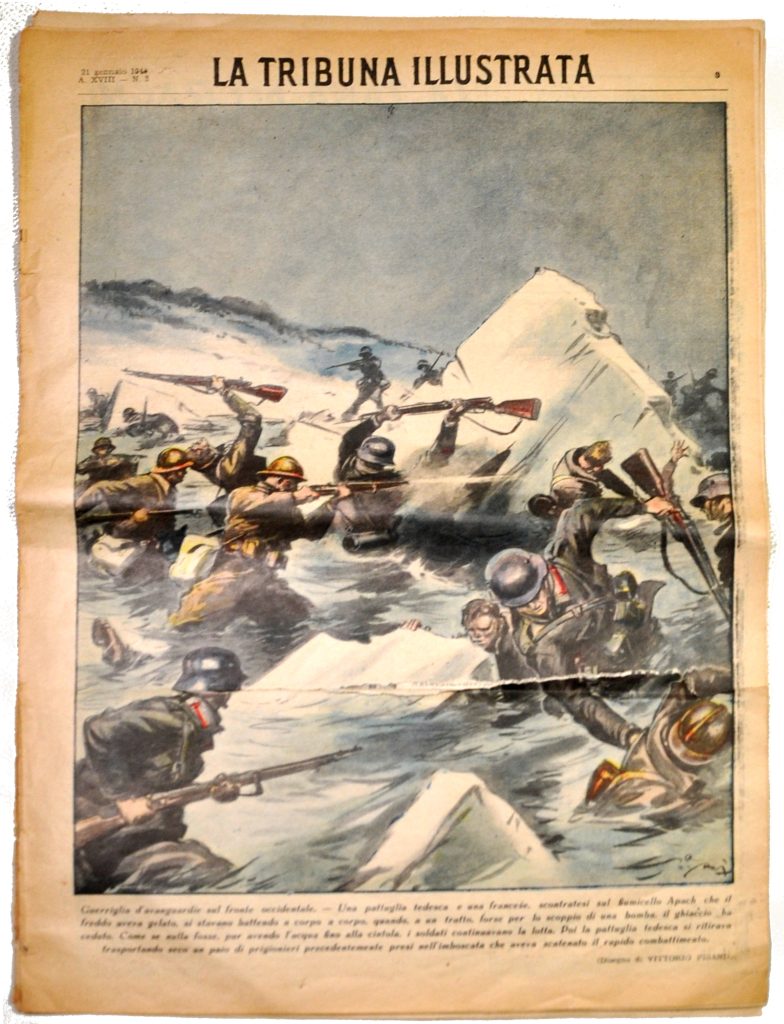

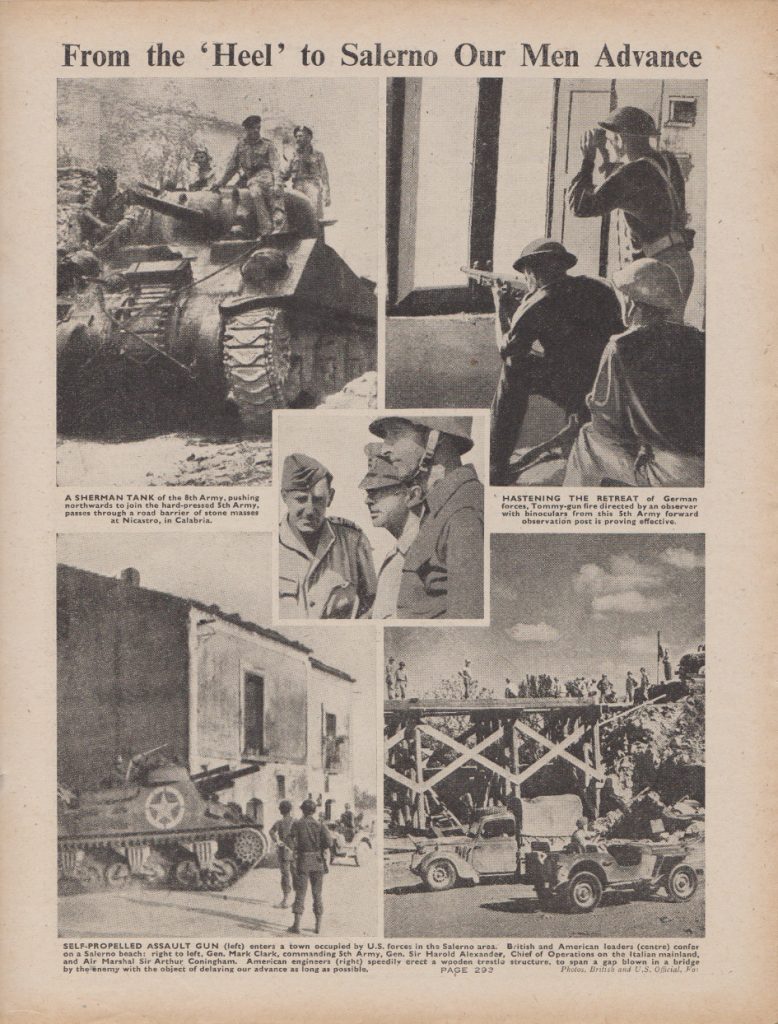

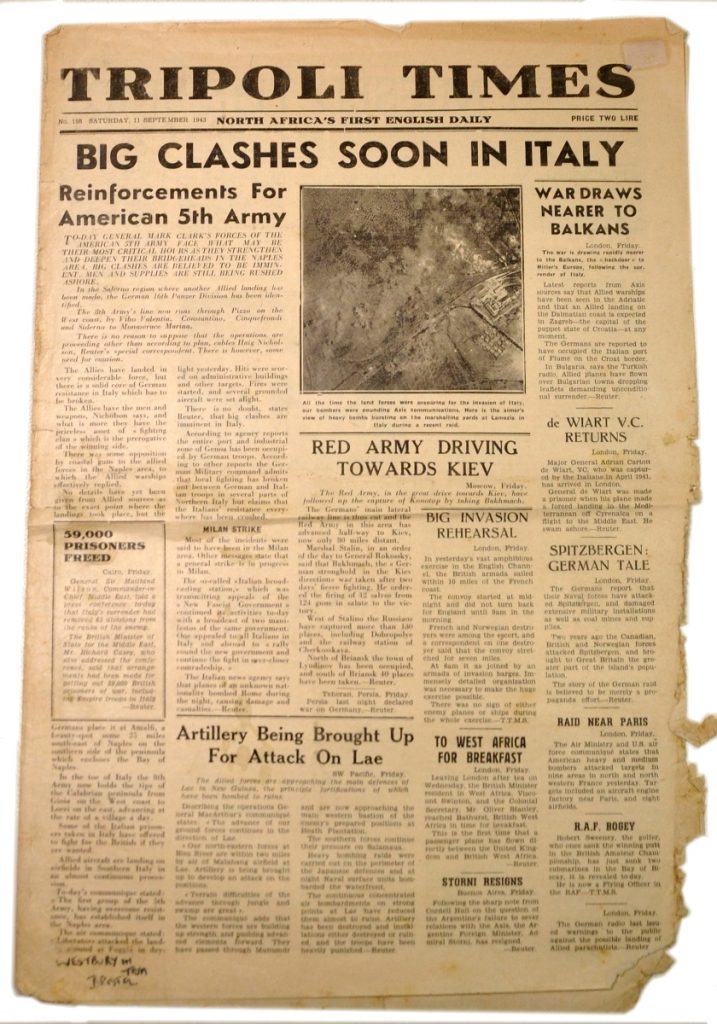

Accounts of the war

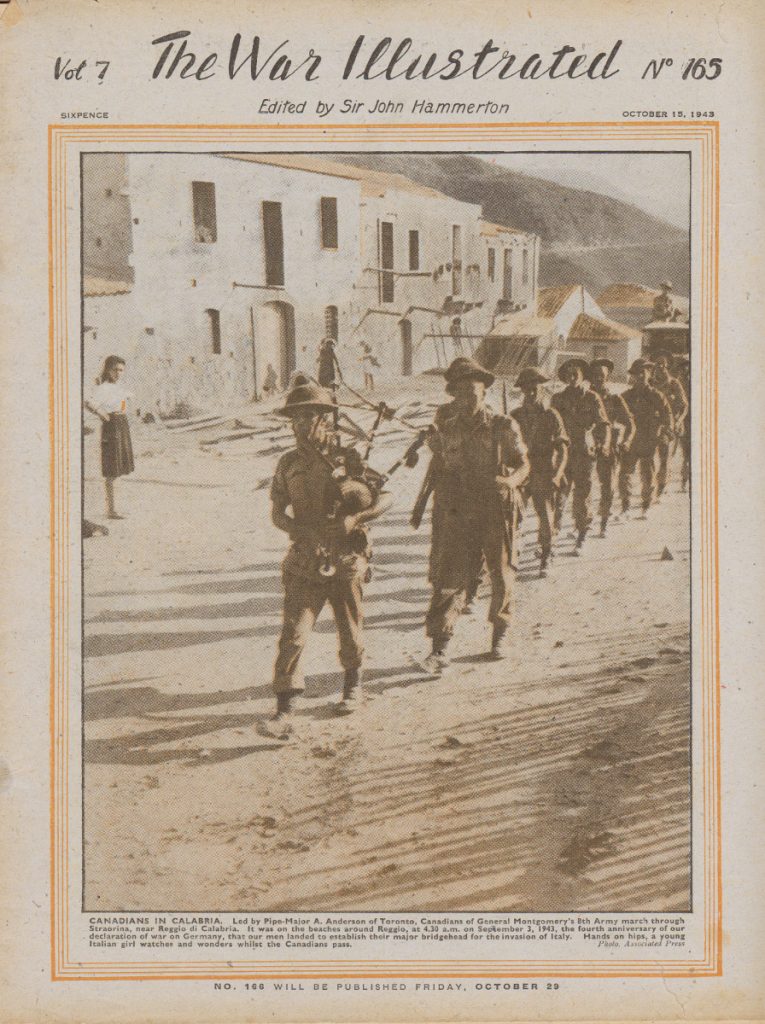

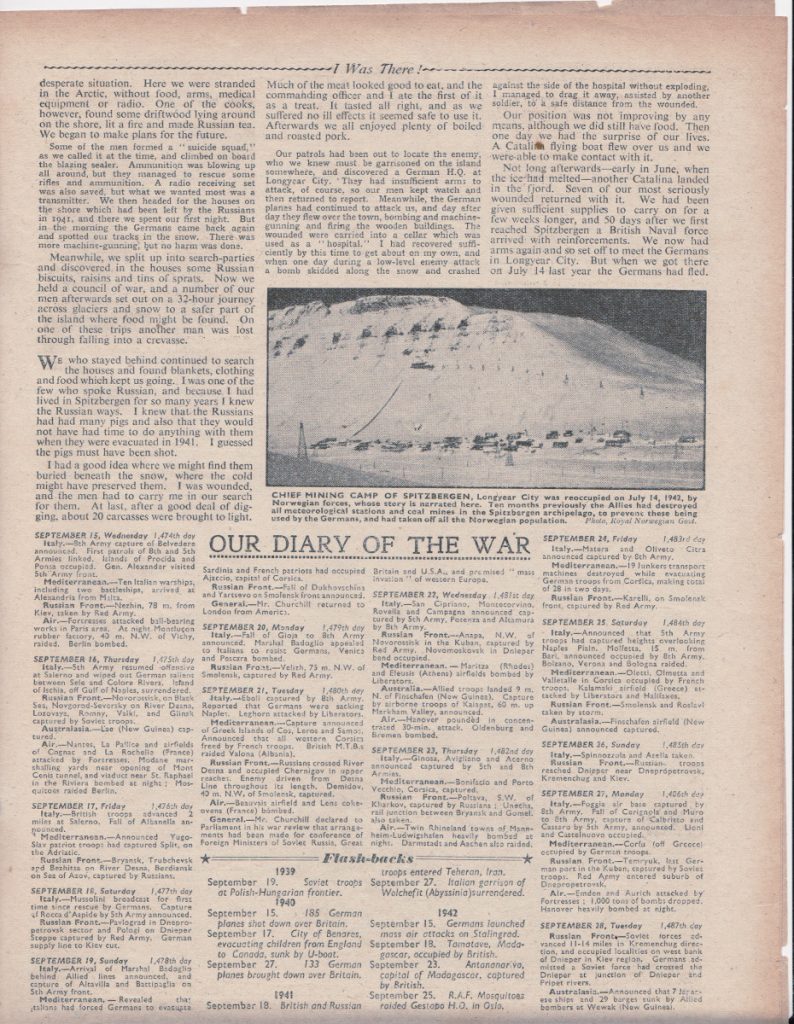

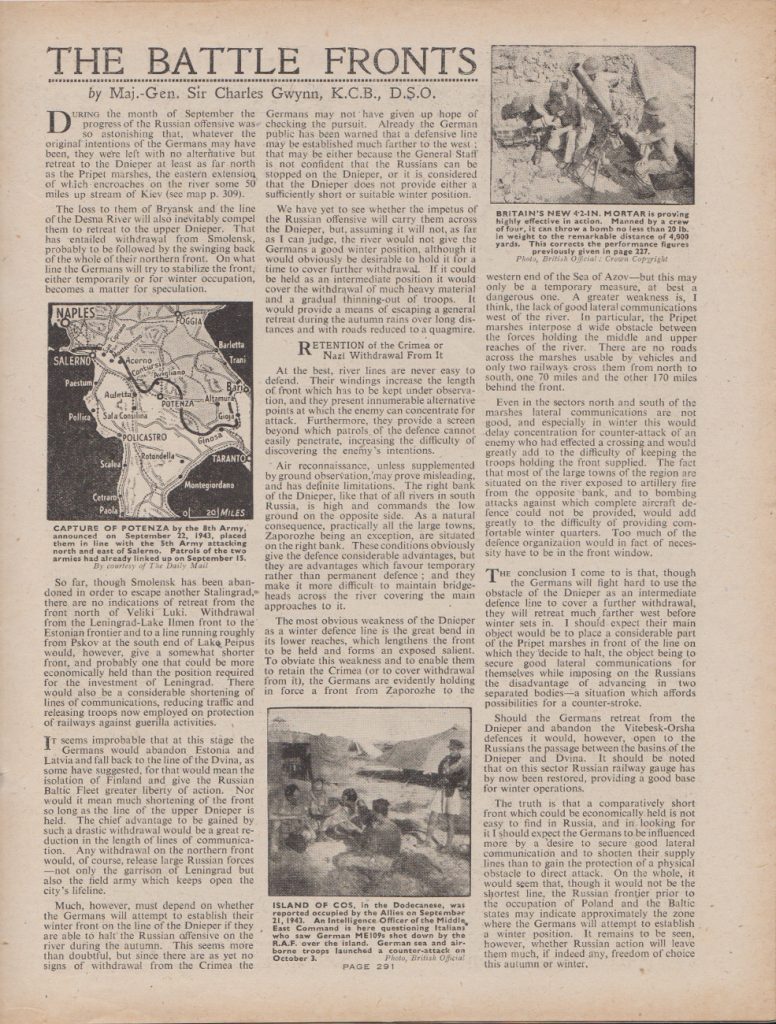

Since before the conflict, the press of both Fronts was actively involved in the propaganda campaigns in support of their respective governments. Publications were certainly subjected, whether directly or indirectly, to the pressure put by governments, which also carried out explicit controls on newspapers. Victories were emphasised, whilst less positive news were downplayed as much as possible.

For the first time war is illustrated with continuity through images, photos and footage, a narration to which contributed such notable personalities as Robert Capa, John Sturgees, William Wyler, George Stevens, Frank Capra, John Huston, John Ford, just to name a few.

The name of a woman really stands out, Clare Hollingworth, English reporter of the Daily Telegraph, who was the first to inform the world about the invasion of Poland, but already a few days before, having crossed the German border, she could report that Nazi Germany was grouping huge numbers of troops and means to the border.

The war clearly monopolised the attention of readers and specific publications dedicated to it were added to the traditional press.

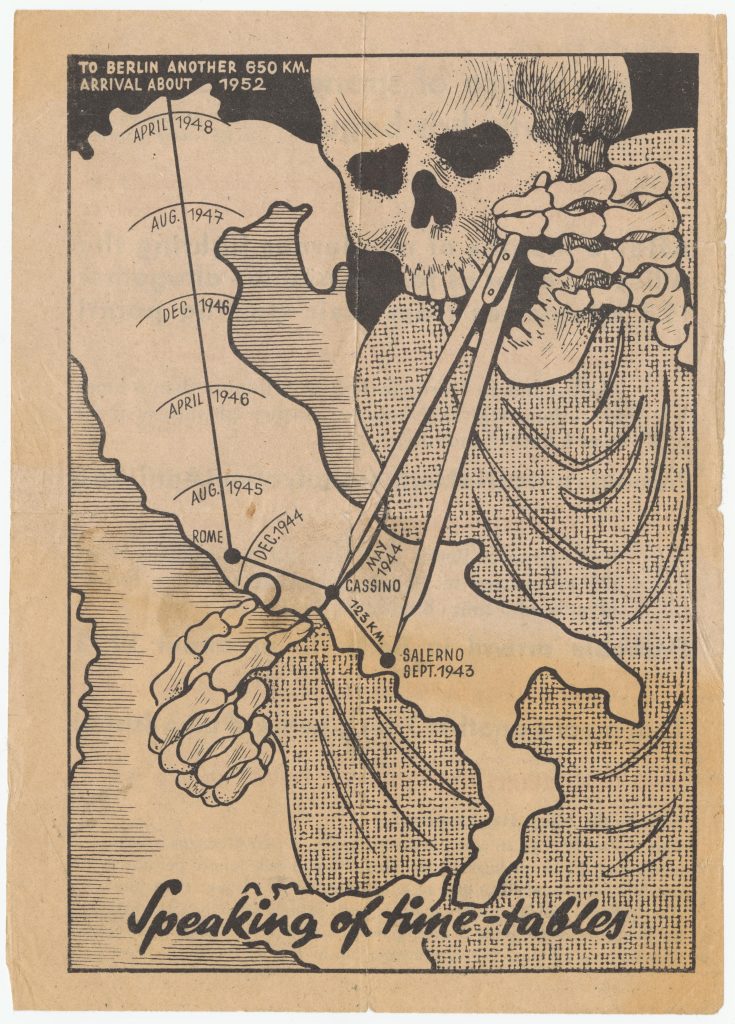

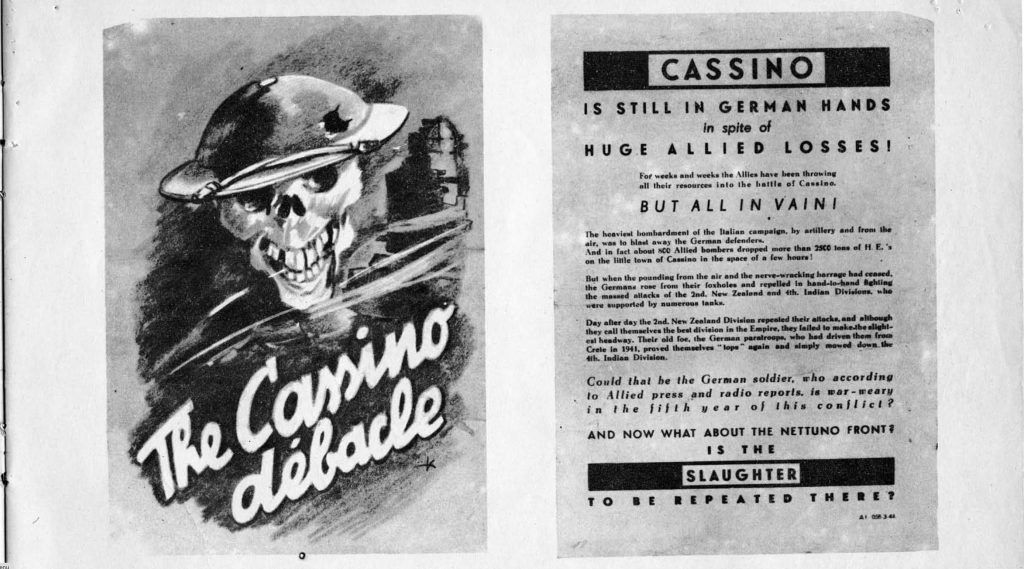

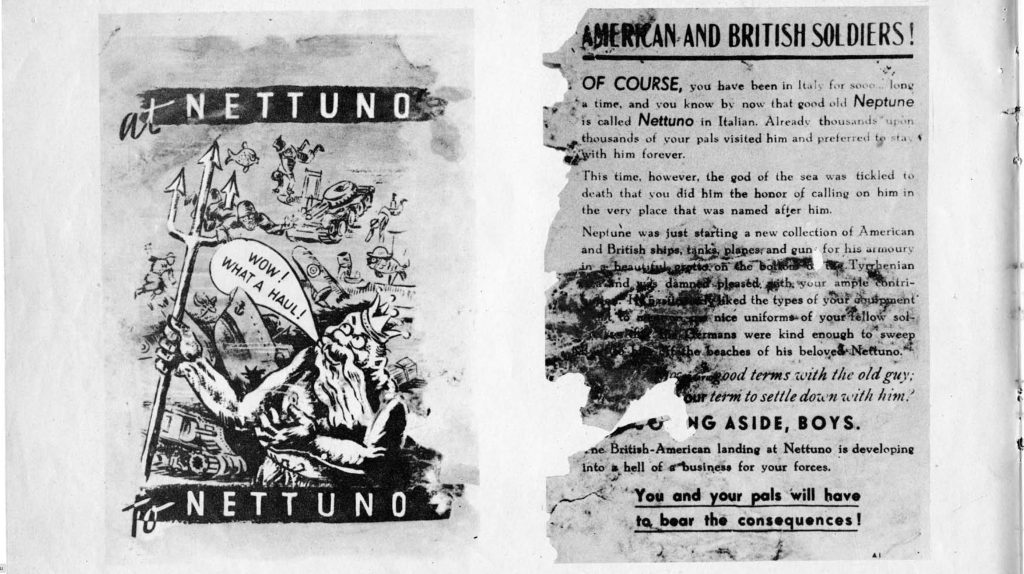

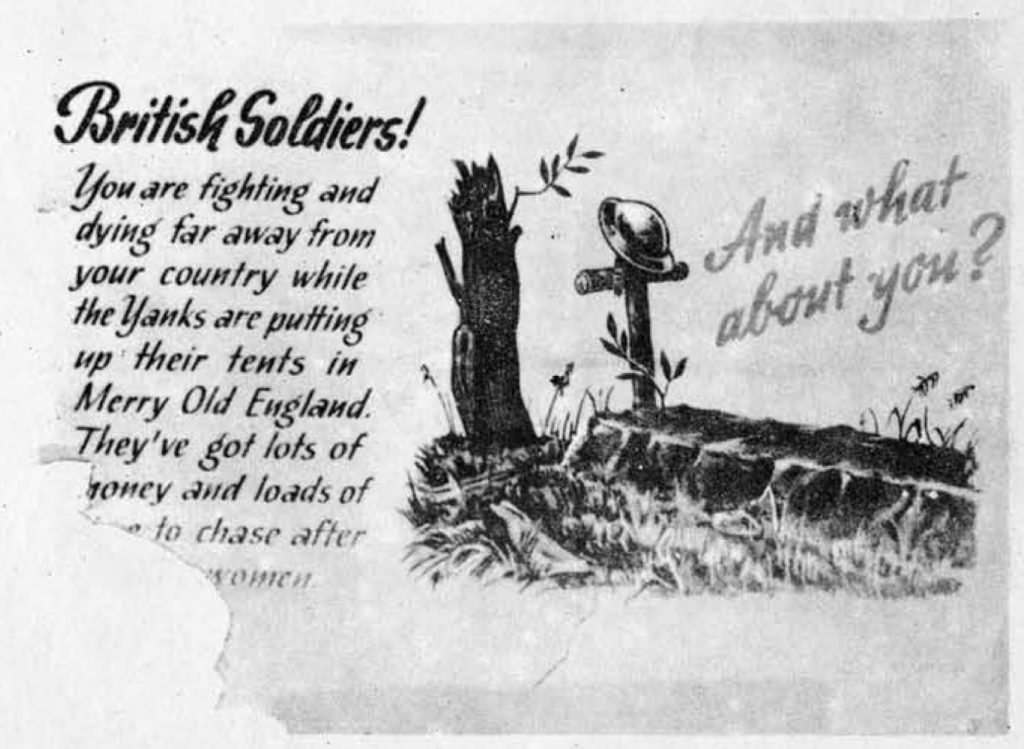

Leaflets against the troops

Another propaganda communication tool were leaflets, widely used on both fronts in order to discourage opponents or civilian populations.

As a matter of fact, it was not uncommon for Americans to drop leaflets on Italian cities so as to urge people not to support the fascist government, thus undermining its credibility.

In this section, instead, we collect some of the posters predisposed to be addressed to Allied soldiers and to weaken their morale.

The theme of the “time” employed by Allies to travel along the occupied zones is recurring. As we can see, with the defeat in Africa and the hardships on the Italian and Eastern fronts, the general tone of Nazi propaganda shifts from an unwavering faith in victory and in the Aryan myth to a rethoric of defense until the last breath.

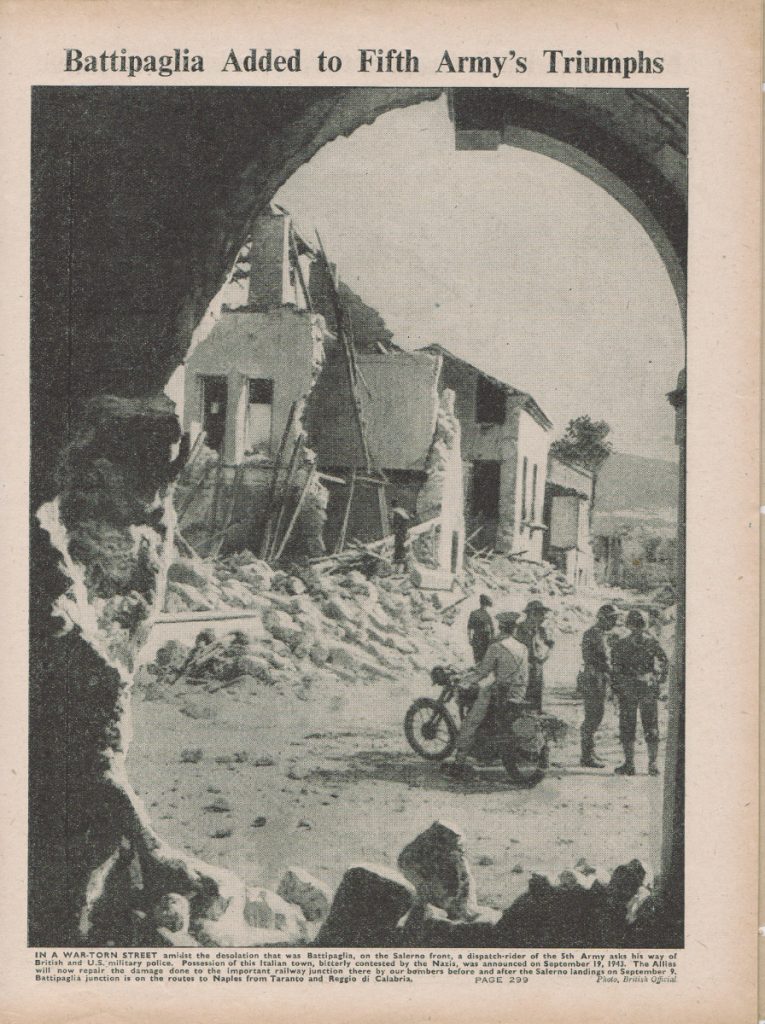

Città di Battipaglia

Città di Battipaglia