Stories, the protagonists’ words

The “History” of ordinary people

The lives of hundreds of thousands of people were crossed by the events of September 1943 and that experience for certain, just as it is for everybody who has witnessed the Second World War, has crystallized in their hearts and minds. A few translated those experiences into pages or left a mark of their own testimony, also thanks to the effort made by researchers who have worked to ensure that these precious testimonies wouldn’t disappear forever with the demise of their custodians.

These are all testimonies of how “History” can overwhelm the life of ordinary people.

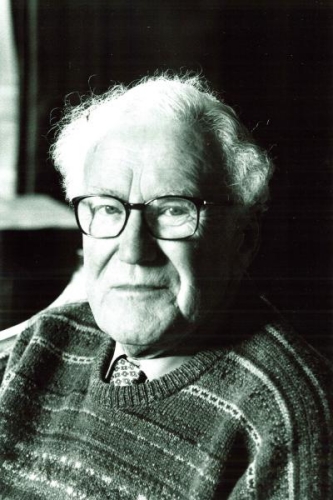

Norman Lewis

Norman Lewis is undoubtedly one of the most eminent witnesses of those months of war and despair. In 1943 he serves the Eighth Army in the Security Field Police and he describes his Italian experience in a book which will later become one of the most renowed accounts of the war: “Naples 44”.

Lewis will become a much esteemed writer, so much so that Graham Greene himself places him among the greatest British writers of our century. His account is obviously focused on his personal experience with the vivid yet tragic scenario of Naples under the Allied occupation, but he also dedicates a long prologue to the experience of the landing.

“This was the greatest invasion in this war so far – probably the greatest in human history – and the sea was crowded to the horizon with uncountable ships, but we were as lost and ineffective as babes in the wood. No one knew where the enemy was, but the bodies on the beach at least proved he existed.”

Two features stand out from his narrative: the wonder when he admires the landscapes and the vestiges he comes across, and, in contrast, the effects of the war that the army, to which he also belongs, has contributed to determine.

September 9

“We saw the twinkle of white houses in orchards and groves, and distant villages clustered tightly on hilltops. Here and there, motionless columns of smoke denoted the presence of war, but the general impression was one of a splendid and tranquil evening in the late summer on one of the fabled shores of antiquity.[…] “

“As the sun began to sink splendidly into the sea at our back we wandered at random through this wood full of chirping birds and suddenly found ourselves at the wood’s edge. We looked out into an open space on a scene of unearthly enchantment. A few hundred yards away stood in a row the three perfect temples of Paestum, pink and glowing and glorious in the sun’s last rays. It came as an illumination, one of the great experiences of life.“.

We drew inspiration from such an evocative image, from the “soldier Norman’s journey” inside the Italy of art and history, to paint a mural, made by the artist Alfonso Mangone, that we placed on the beach of the Roger sector in Battipaglia, in order to remember, not with the images of the tragedy, but with the amazement of the human soul that captures the essence of an ancient land.

On the other hand, Norman Lewis is astounded by the events of the war, by its rawness and its effects on defenceless civilians and he is aware that all of this isn’t just a mere product of the destructive ineluctability of the armis confligo, but of the determination of men.

“At Battipaglia it was all change, with an opportunity for a close-quarters study of the effects of the carpet bombing ordered by General Clark. The General has become the destroying angel of Southern Italy, prone to panic, as at Paestum, and then to violent and vengeful reaction, which occasioned the sacrifice of the village of Altavilla, shelled out of existence because it might have contained Germans. Here in Battipaglia we had an Italian Guernica, a town transformed in a matter of seconds to a heap of rubble.“

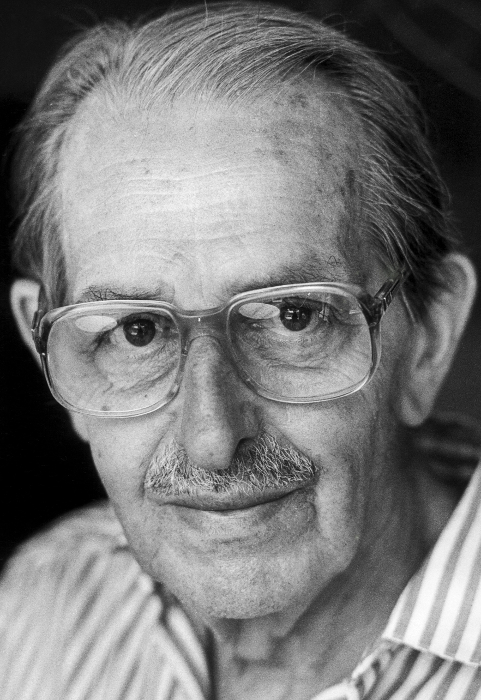

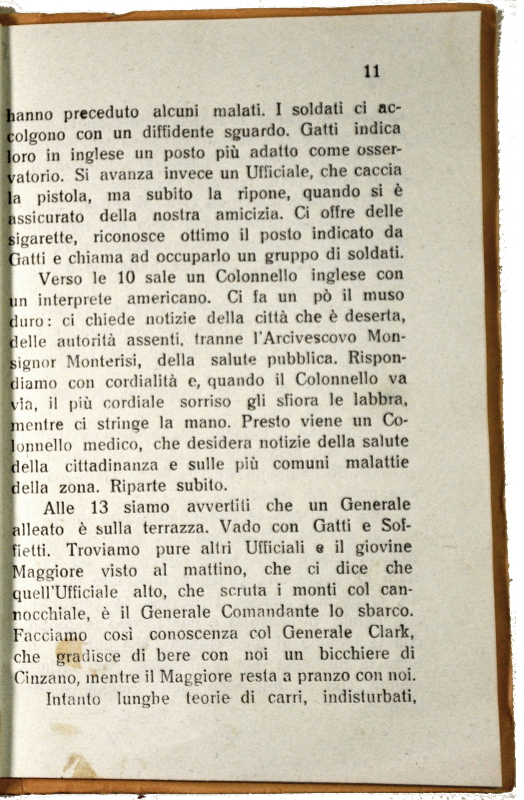

Arturo Carucci

Arturo Carucci is the young chaplain of the Salerno Sanatorium in 1943. He was born in 1912 and he is 4 years younger than Norman Lewis, who boarded one of the ships that Arturo can see from the hospital approaching the roadstead of Salerno.

During the course of “Avalanche” his position too will turn into one of a “warrior” in defence of the patients housed in the facility. The hospital is strategically located on a hill of Salerno, just alongside the front line between the Germans and the British, that’s why it becomes a battlefield where General Clark too, as told by Father Arturo Carucci, makes an appearance.

The young Chaplain and the other executives will agree to embark on a sort of “wandering in the desert” with the purpose of getting the ill people and the personnel to safety from Salerno to Naples, through the Chiunzi Pass, which leads from the Amalfi Coast to Nocera. The writer will gift us with a story in 1945 about that experience.

The Salerno Sanatorium, in the words of Carucci, becomes a place where Germans and British alternatively pass through, almost like the stage of De Filippo’s comedies, with the patients and the staff caught in the middle, while uncertainty hangs over them.

The Fragile Memory of Senza Rossetto

The Mubat association has cooperated with the Senza Rossetto Archive (literally, “Without Lipstick Archive”) by realising two interviews with Gerardina Di Cunzolo and Rosa Alfano of which we publish here two brief extracts. The two women tell, with dissimilar points of view, the war period and the life ensuing from it.

The “Senza Rossetto” Archive created in 2016 a journey inside the imagery of women at the turn of the Second World War. One of the results of the end of the war was the decision, reached during the experience of a provisional government in Salerno, to let the Italian people have the right to autonomously determine their own future. In 1946 the Monarchy-Republic Referendum was held by universal suffrage, and for the very first time women throughout Italy could vote (those who were of legal age, 26 years old).

Gerardina Di Cunzolo_2 from Regesta.exe on Vimeo.

Rosa Alfano from Regesta.exe on Vimeo.

Archivio Audiovisivo Senza Rossetto

Rosa Alfano recalls in this short clip the political and social climate in Battipaglia during the twenty years of fascism.

Parallel Lives

Walter Archibald Elliott and Carlo Carucci

“This publication was created not only as a war diary, but also to tell a piece of contemporary history in which visions of identity were generated and nurtured among people (as well as mutual loyalty). It also wants to offer some messages in favour of the control of human conflicts and the positive consequences of the search for peace“.

With this preface Lord (Walter) Archibald Elliott introduces his account of the experience in Salerno: “Esprit de Corps – A Scots Guards Officer on Active Service 1943 – 1945”.

Elliott, who is going to become an eminent jurist on his return to his homeland, is one of the thousands of boys coming from the British mist that are being catapulted from the bowels of the Allied ships onto the Italian beaches.

Elliott has turned 21 since a few days, on the 6 September, when his war experience in Italy begins. As he writes in the book, the operating plan of the 201st Guards Brigade was rather muddled. When still at sea it was communicated at first that they would have supported the Americans in an attack on the Naples airport, but later on the “over-optimistic” plan was changed and a landing site north of the Tusciano river was assigned.

Everyone aboard, summoned for the last briefing, listens to a sudden announcement:

“The ship’s megaphone blared at full volume and announced in deep, gruff tones to an astonished audience that, under the command of Marshal Badoglio, the Italian army had surrendered. This Italian army of 35 divisions was now to come to the aid of the victors. It sounded like a last minute stroll and shouts of ‘The war is over! The war is over!’ could be heard from all over. Men stumbled along the gangways to go and tell the dramatic news to their companions that had stayed asleep. Those who had secretly hoped for a cancellation of tomorrow’s attack suddenly felt very brave again and even cheated of worthy opposition.[…] We all gathered on deck in good spirits despite a skeptical veteran sergeant next to me saying: ‘Jerry won’t let us get away with it, sir!’“

Lord Archibald Elliott’s diary is very interesting due to the fact that, beginning with the landing at the Tusciano area, in the Roger sector, he recounts the story of his unit, which worked in the zone of Battipaglia and, in addition, he also offers a comparison with the narrations of other protagonists, like the one of Carlo Carucci, a professor in Olevano, who describes the development of the battle as seen through the eyes of Italian civilians from his residence on high ground.

Elliott and the Scots Guards, to which he belonged, follow a wartime “itinerary” among the most critical ones, the direction to Battipaglia. The fight for the tobacco factory, the station and the German counterattack, with the unexpected turning point of the capture by the Germans and the daring escape to Olevano are described in his account.

There, where Carlo Carucci observes the war actions, the young soldier is initially triumphantly received as a “liberator”, then, once people realize his condition as a fugitive, he is hidden by the inhabitants of Olevano in the St Micheal cave, an inaccessible place, far away from the town, where the citizens of Battipaglia had found shelter on the run from the bombings.

A remarkable help was received by the Italian soldiers holed up in the caves. For every Italian that he meets Elliott has words and comments that occasionally result in quaint depictions, but that are also of sincere appreciation.

Max Melamerson, Riccardo Dolker and Jacob Sturm

In Vietri sul Mare and Ferramonti di Tarsia the stories of three people intertwine, whose lives get devastated by the Second World War. The lives of the first two people cross in Vietri, whereas the second and the third both pass through the Ferramonti internment camp: their lives will then follow three different paths, but fortunately they will all survive the conflict.

Max Melamerson, a Jew from Poland, arrives in Vietri to escape the tense atmosphere and thanks to his entrepreneurial ability he manages to set up a business which contributes to the history of Vietri’s ceramics. Richard Dolker was entrusted by him with the manufacture’s artistic production at a time when Northern European artists were coming to Vietri and creating from scratch a new artistic community: Bab Hannasch, Elsie Schwarz, Liesel Opel, flanked to young local potters.

The Vietrese production transforms blending the colours of the South with the fascination of the traditions of the North. There is a switch from an essentially industrial production to an artistic one that originates the current art of the Vietrese ceramics. Max is skilled and he also manages to have great relations with the authorities, he even manages to become a supplier for Palazzo Venezia in Rome. The partnership with Dolker ends because of some misunderstandings, the factory is shut down as a result of racial laws and Melamerson with his wife Flora end up interned in the Ferramonti camp. For a period of time, young Jacob Sturm too ends there.

In an interview (CDEC Archive reference) recorded in Jerusalem by Liliana Picciotto in 1991, Jacob tells how his family, after having arrived in Milan in 1939, was firstly deported to Ferramonti, where, however, they opted for the “free internment” and therefore moved to Pavia. Then the time came for them too to be arrested. Jacob was separated from his parents, whom he never saw again, and later sent to Birkenau, where he reunited, not for long, with his brother, subsequently killed in the camp.

Dolker, after working in another ceramic laboratory, will come back to Germany, but he’ll be recalled to the army and will serve on the eastern front, where he’ll get captured. He’ll return to Germany at the end of the war.

Melamerson went back to Vietri and tried to recover some of the things that had been taken from him. He eventually moved to Rome.

Jacob escaped his execution towards the end of the war by fleeing into the woods.

Città di Battipaglia

Città di Battipaglia