The liberation of the camps and the Holocaust in Rome

Racial discrimination and the origin of concentration camps

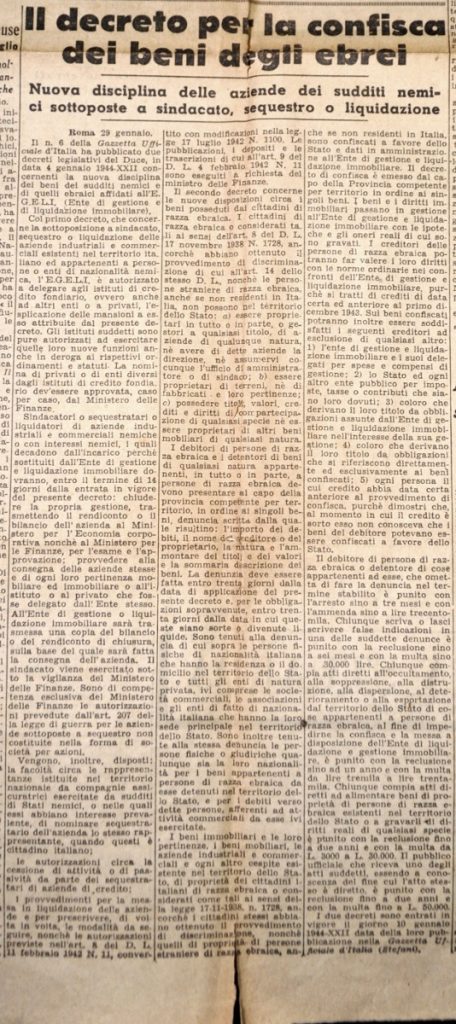

Since 1938 Italy had adjusted its policy to the “defence of the race“, borrowed from the German ally advocating it, with the outrageous laws promoted by Mussolini and countersigned by the Savoy. Jewish kids were forbidden to attend schools, Jewish staff was purged from administrative and public offices, all their assets were confiscated. The E.G.E.LI. (Ente di gestione e liquidazione immobiliare) was established following the Royal decree 9 February 1939, n. 126, to handle the management and the liquidation of the Jewish assets.

The censuses conducted at that time by the Italian administration turned out to be pivotal for the deportations carried out by the Nazis, precisely from 1943.

An even worse fate befell foreign Jews, unless they had arrived in Italy before 1918.

Oftentimes they had emigrated from their countries precisely to escape German persecution, but in 1938 racial laws required them to leave Italy under penalty of arrest.

There were distinctions between subjects of enemy countries and Jewish citizens of countries where racial policies were implemented, just as detention in concentration camps or “free” internment were provided. Hence, in 1940, 15 dedicated concentration camps were created all over the country, primarily for the detention of foreign Jews, but also for other opponents of the regime.

For a broader description of the persecutions of Jews in Italy we advise you to take a look at the online exhibition of the Shoah Museum realised by the CDEC Milano.

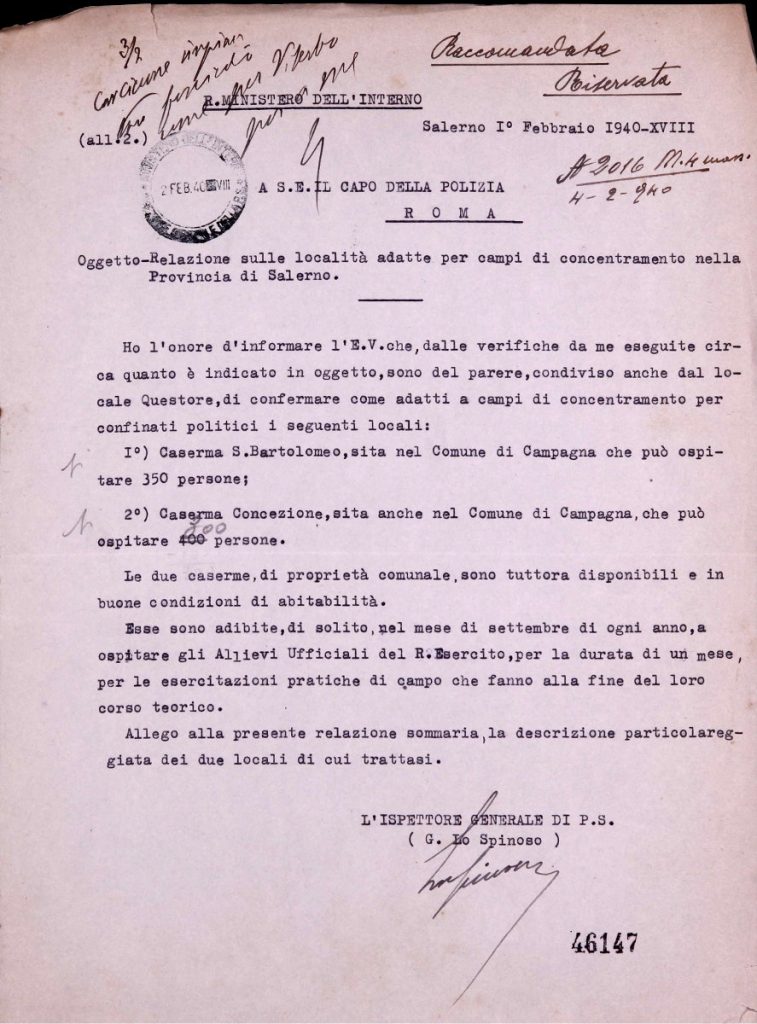

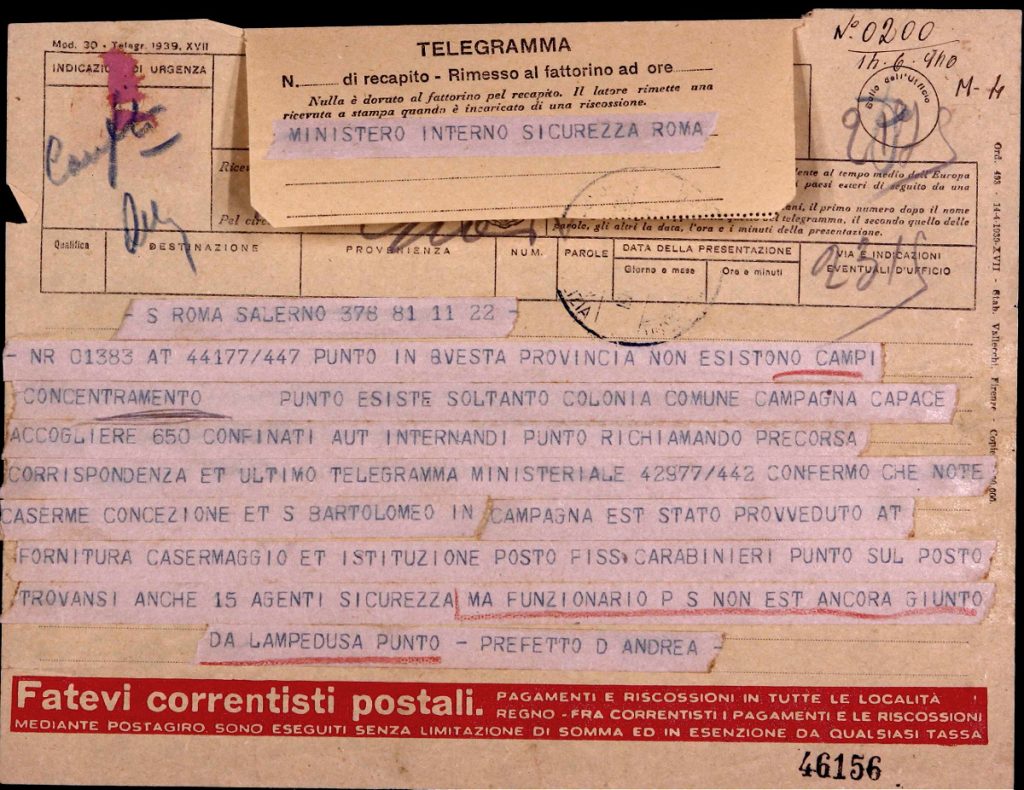

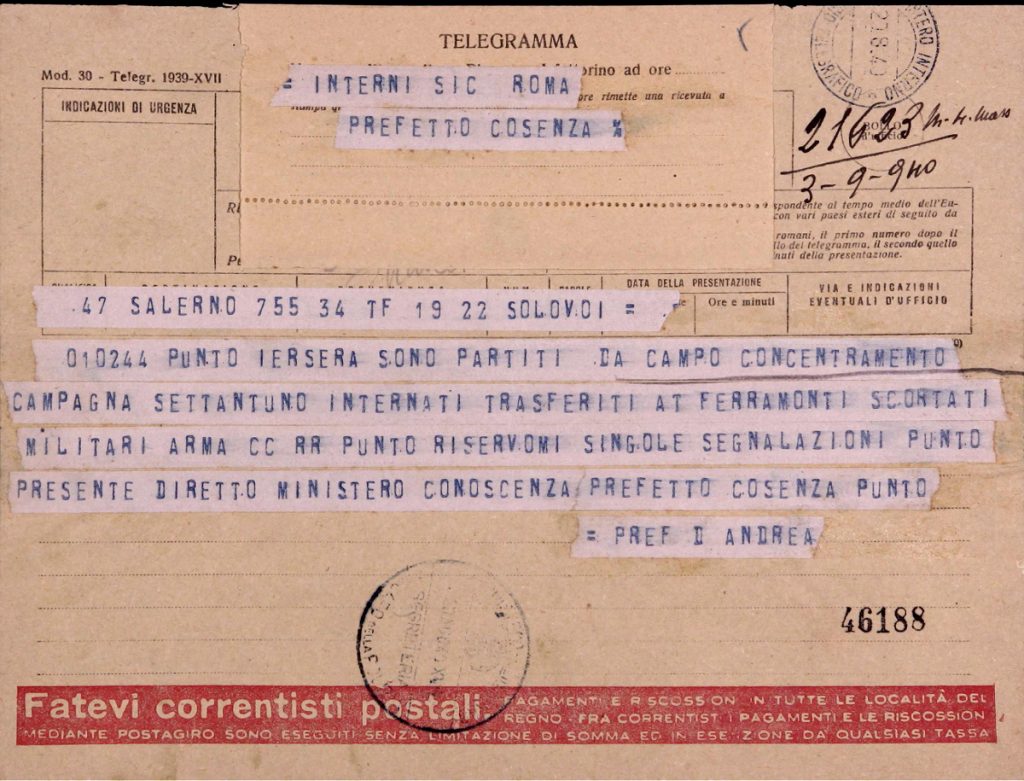

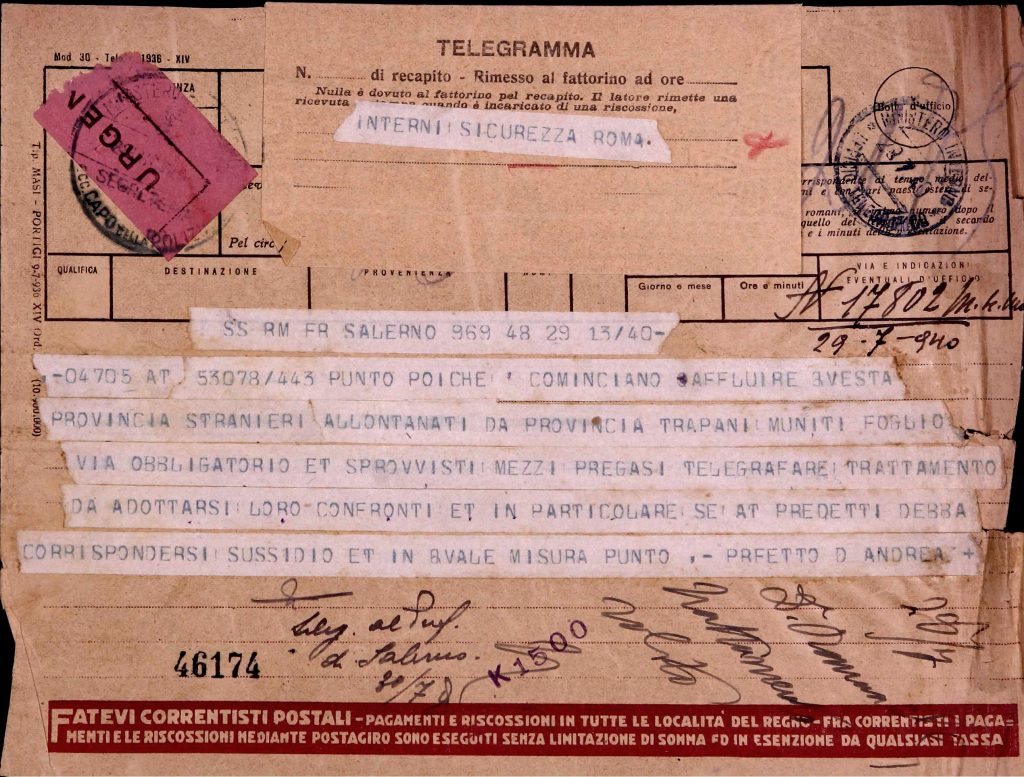

The following documents come from the Central Archives of the State (riferimento: ACS, Massime M4, b.134, f.16, ins. 36-Salerno). They contain the initial activities related to the internment camp located in Campagna, an isolated comune of the province of Salerno. The report on the possible locations to find and the indications of the Prefect D’Andrea on the presence of a colony of prisoners (1940) testify to the preparatory work arranged by the fascist government.

ACS – a report on potential places where to allocate concentration camps, 1st February 1943

ACS – Prefect D’Andrea’s telegram about detention centres in the Salerno area, 10 June 1940

Ferramonti concentration camp

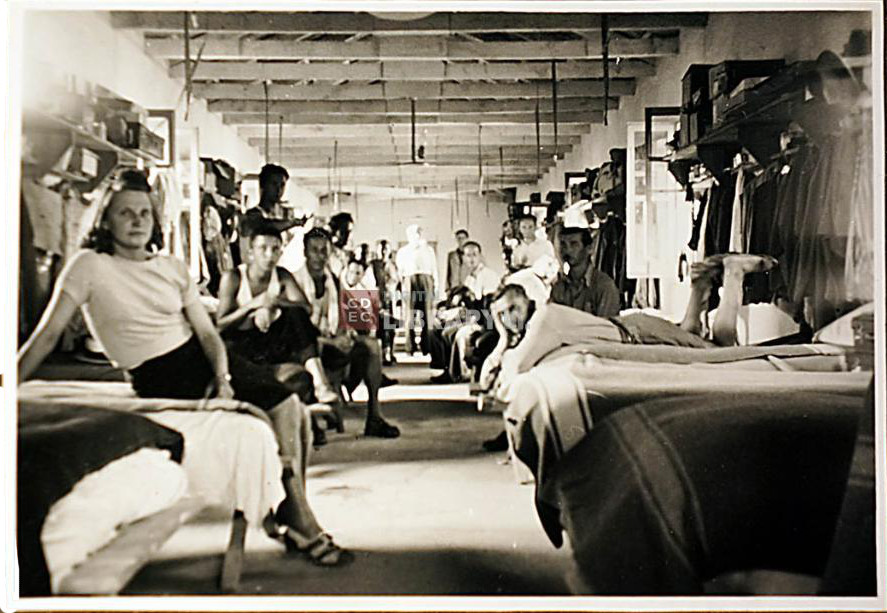

The internment camp in Ferramonti di Tarsia, near Cosenza, was the largest in Italy because of the number of people interned. The Jewish prisoners equipped themselves with an internal organisation and some of them kept staying in the camp even after its liberation, although this must not mislead about the conditions of the place, that were still very harsh. The poor sanitary conditions and, more generally, the environment in the camp exacerbated the already sad situation of racially-motivated deprivation of liberty.

Israel Kalk, a Lithuanian arrived in Milan in the 20s, didn’t fall within the group of foreign Jews subject to deportation and due to his condition he was able to set up an assistance network for the underdog until 1943, when he found shelter in Switzerland. On his return he devoted himself to gathering testimonies and memories of the prisoners in Ferramonti. From his documentation the realistic view of the life in the camp becomes apparent.

The conditions of the camp were unhealthy, its population exceeded two thousands units and only its liberation, in conjunction with the liberation of the South of Italy, spared the people from similar consequences to those suffered by the prisoners of other camps, headed towards German and Polish concentration camps.

In Ferramonti, as stated before, it was possible to plan activities for children also thanks to Israel Kalk’s organisation and in March, on occasion of his visit, people even put on a concert.

In the 30s in Italy there were lots of artists that had escaped the heavy situation in Northern Europe, but many nevertheless ended up in camps. Some musicians among them helped making other convicts’ days a little less heavy. Moreover, an interesting online exhibition is dedicated to a few of them and to the concert in Ferramonti.

Ferramonti was the first concentration camp to be liberated by the Allied British soldiers that were passing through Calabria, on 14 September 1943. We owe to them also the following footage documenting the departure of some detainees. This video appears to be assembled in order to give a favourable representation of the liberation of the camp.

IWM – footage filmed to document the liberation of the camp in Ferramonti by the British army.

The conditions of the camp are evidenced by the photos available online on the Digital Library of the CDEC (Center of Contemporary Jewish Documentation) in Milan, of which we show a small selection to document life in the shacks as well as the presenece, in seclusion, of many children.

These pictures, however not even remotely comparable to those depicting the camps in Germany and Poland, must be interpreted in light of the bigger picture: people who had committed no crime at all found themselves deported from their places of residence and deprived of their fundamental freedoms.

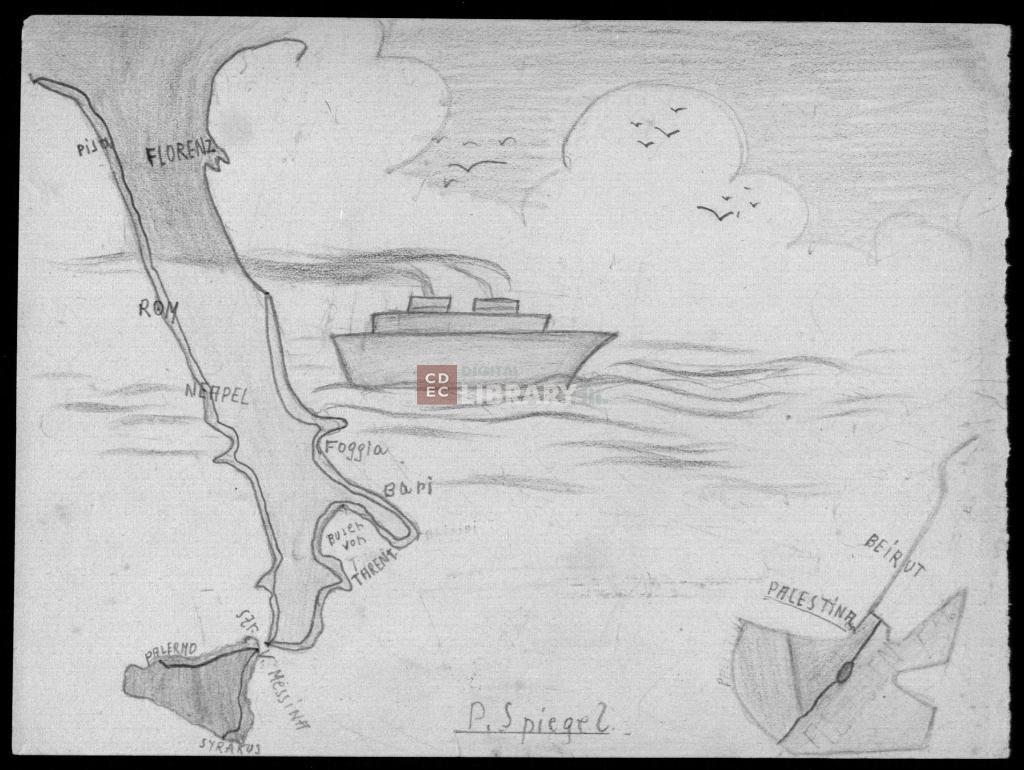

Digital Library CDEC – Ferramonti, kids drawings – Isreal Kalk Foundation busta 7 , fascicolo 109

Campagna internment camp

In Campagna, in the province of Salerno, the Ministry of the Interior set up another gathering place for Jewish refugees in the middle of 1940.

The camp, initially located in two barracks, remained active until the arrival of the Allies in September 1943 in the course of Operation Avalanche. Internees in those days had already managed to leave the barrack where they were being held.

Despite the refurbishment preceding the opening of the camp, the spaces were in some cases definitely insalubrious, since they were underground, and one of the two barracks was vacated and condemned because of some collapses.

Sanitary facilities were in reduced numbers and largely insufficient for a population that over the years of activity had exceeded the limits allowed. In exceptional cases some internees were permitted to rent furnished rooms where, for a short time a day, they could go wash themselves.

This might suggest that in Campagna the detention regime was presumably slightly less strict than elsewhere. Furthermore, being located in two structures within the town, a partial integration with the local community was favoured.

Nonetheless, this was still a regime of compulsory detention of several men in unhealthy conditions.

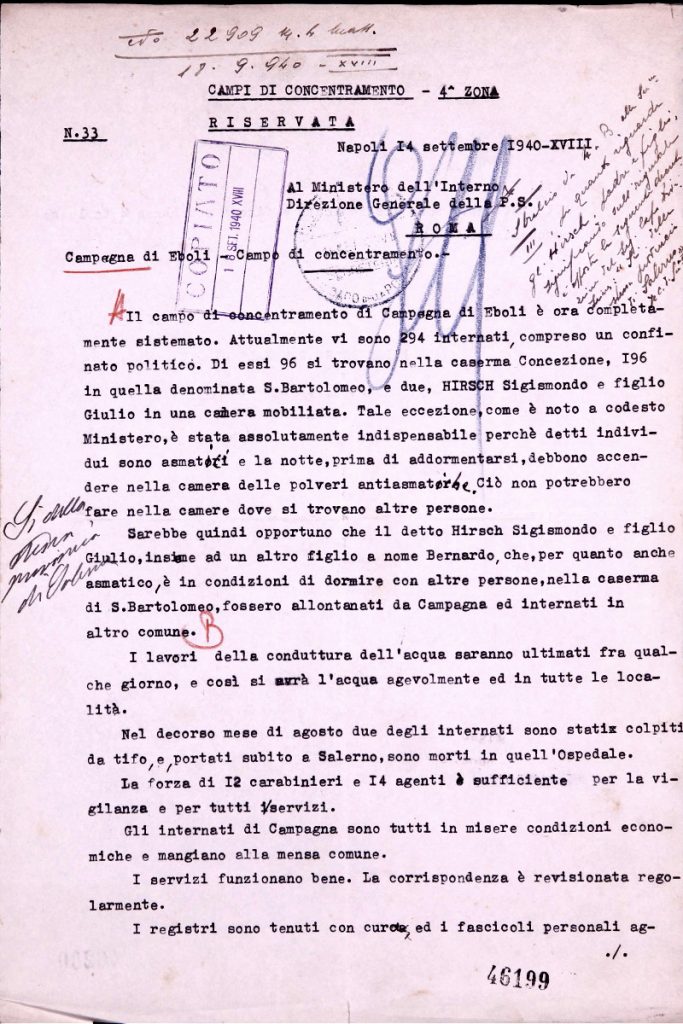

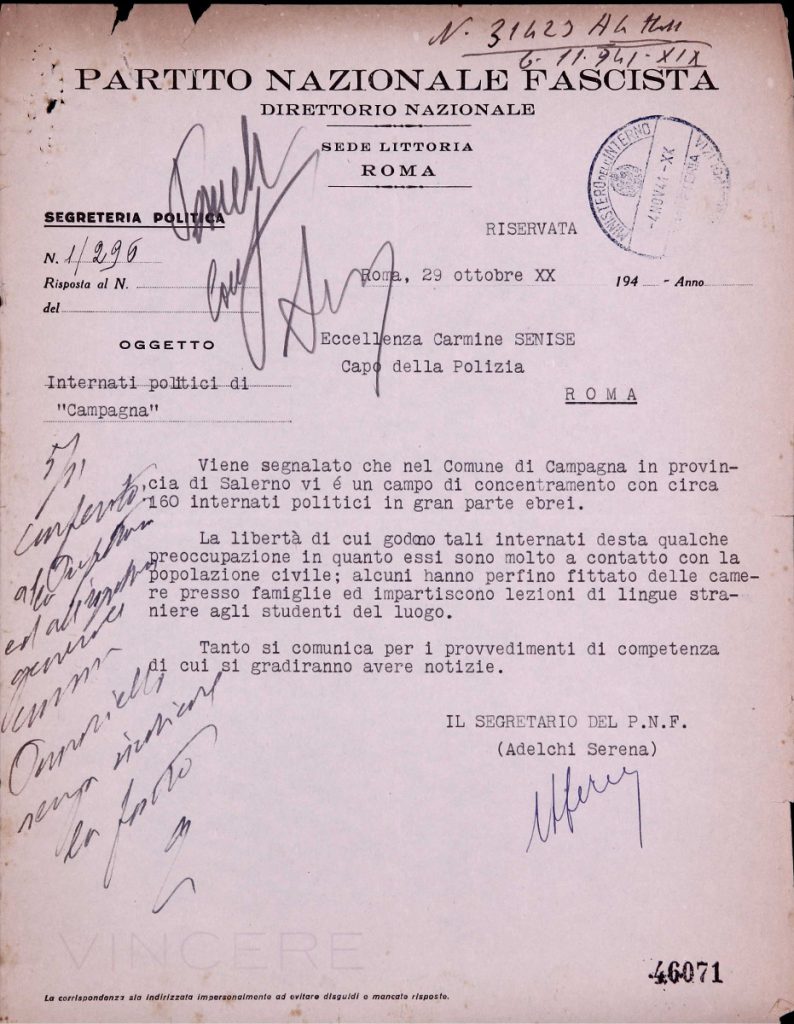

From dossiers at the Central Archives of the State it appears that the whole situation had given rise to some concerns in Rome to the extent that a request for clarification was sent by the PNF (National Fascist Party) to the local authorities.

The report that we publish highlights, albeit in the extreme conciseness of the text, that living conditions were suboptimal, or rather unsafe for the life of the inmates.

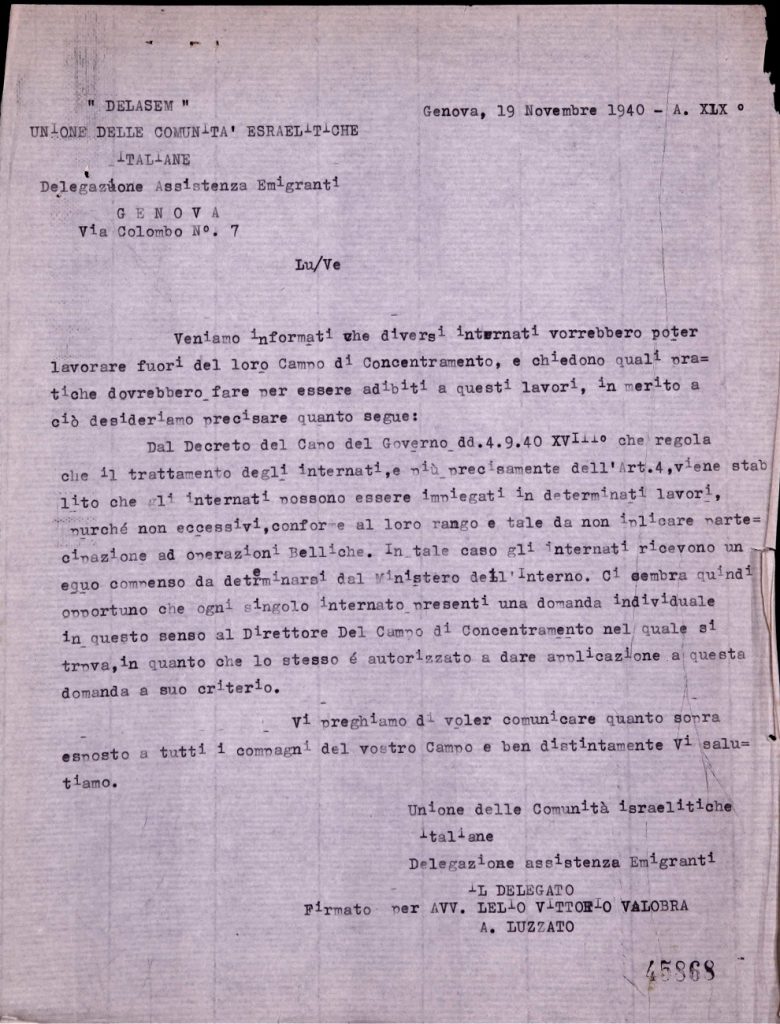

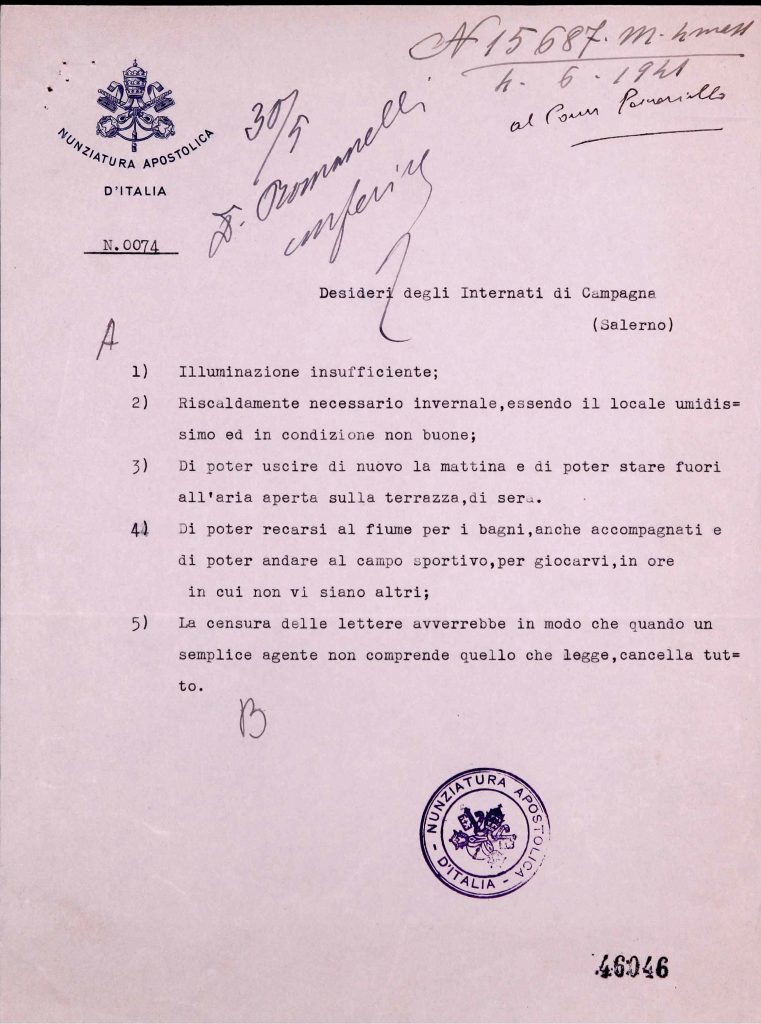

As a matter of fact, some requests were sent, such as those by the Delasem (Delegation for the Assistance of Jewish Emigrants) and the Apostolic Nunciature following, for the purpose of advocating the improvement of prisoners’ living conditions.

ACS Delasem requests for internees in Campagna

ACS Apostolic Nunciature call for action for the inmates in Campagna

Requests were often simple, like the one for a stronger lighting. Other documents kept in the State Archives underline just how there were only two light bulbs, poorly functioning by the way, for large dormitories. Another peculiar request was for censorship to be implemented by troopers able to clearly understand the letters, considering that the inspectors’ ignorance resulted in an exaggerated censorship for the correspondence.

CDEC Digital Library – Foundation Israel Kalk – David Heger and Emil Singer perhaps in the Campagna camp, where David Heger was confined from September 1940 (1940 – 1943) rif. 283-s039-005

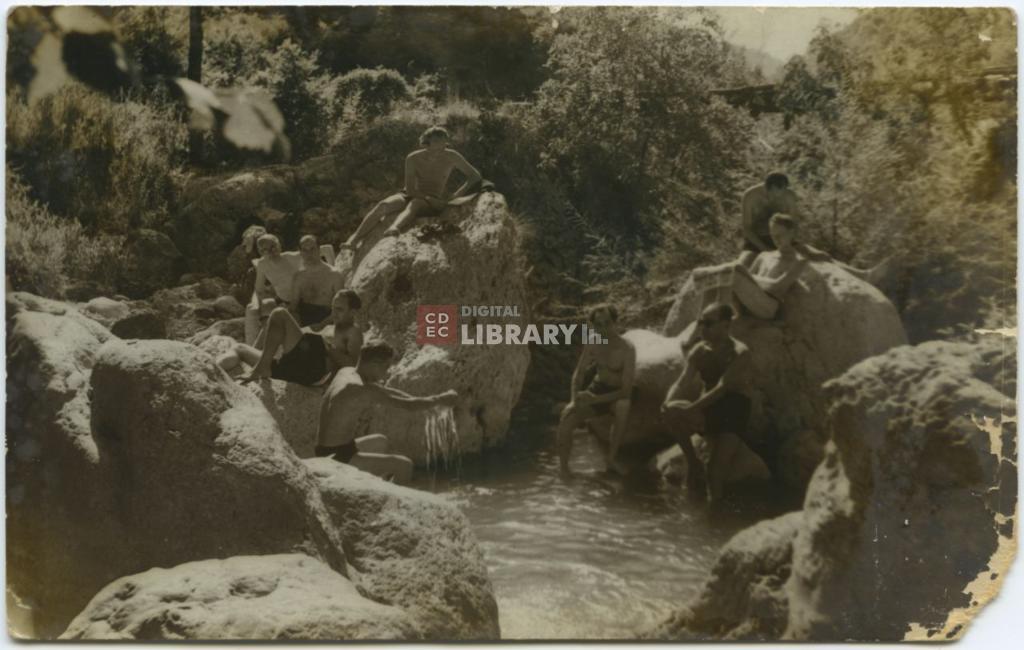

CDEC Digital Library – internees at the river mentioned in the Apostolic Nunciature’s request. Campagna (summer 1941) rif. 283-s039-003

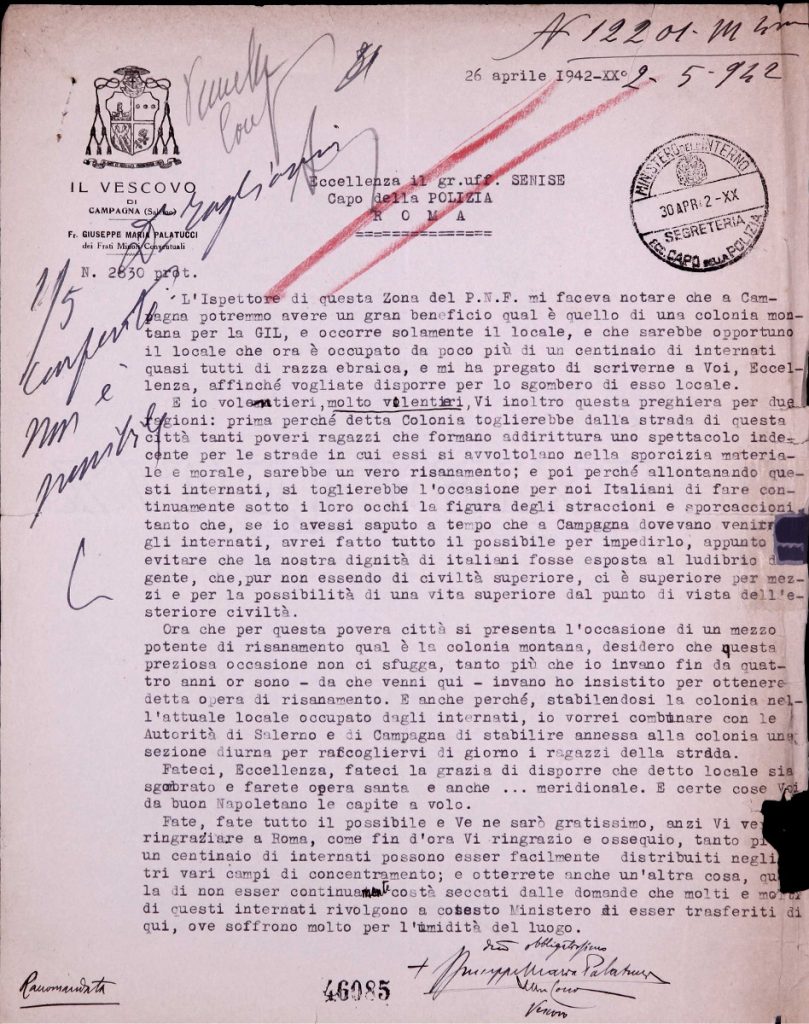

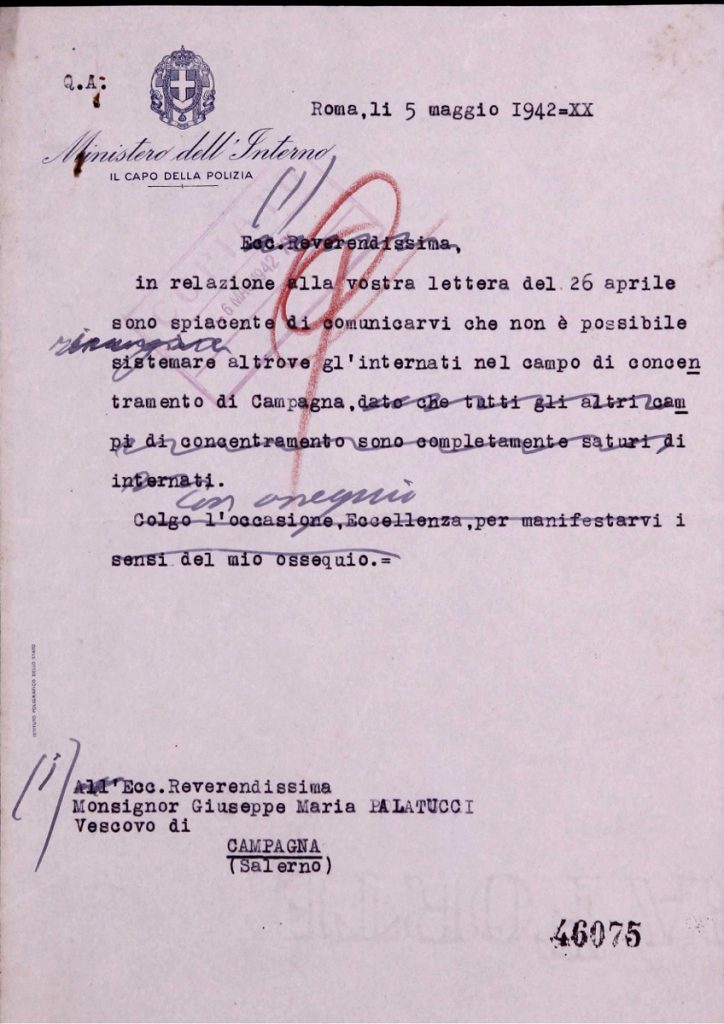

ln 1942 the Ministry receives a request from the then Bishop to evacuate the camp in order to dedicate the barrack employed to the gathering of kids without a family. The request was denied.

ACS – request by Monsignor Palatucci to transfer elsewhere the Campagna detainees

ACS – denial of the request by Monsignor Palatucci 1942

The two following photos describe the documentation above, that is Monsignor Palatucci’s visit to the camp in Campagna and the foreign internees, whose sober and decent appearance, despite the harsh condition of confinement, is at odds with the look of local children.

CDEC Digital Library – Monsignor Palatucci visiting the camp (October 1940) rif. 283-s039-002

CDEC Digital Library – Aron Windwehr in Campagna, side by side with a kid (1940-1941) rif. 647-030

CDEC Digital Library – Aron Windwehr with other men in Campagna (1940-1941) rif. 647-018

In the first photo, welcoming the Bishop, Davide Wachsberger, a rabbi from Fiume of Polish origins. He was transferred in 1941 and died in 1942. The place of death is uncertain. According to the source CDEC he died in Fiume; on the basis of insufficient documentation ACS according to Gabriele Rigano he died interned in the camp in Quero, Belluno.

Aron Windwehr, the man portrayed in the last two pictures, after the detention in Campagna managed to move to Rome first and then to Milan, he tried to emigrate to Switzerland but was not accepted. He was imprisoned in January 1945, incarcerated at San Vittore, where he was then finally freed after the German escaped (CDEC source).

Rome and the consequences of the Allied advance

The landing at Salerno and the Allied victory prevented, apart from some reprisals taken by the Nazis during the conflict, Jews and opponents living in the South of Italy from suffering worse consequences.

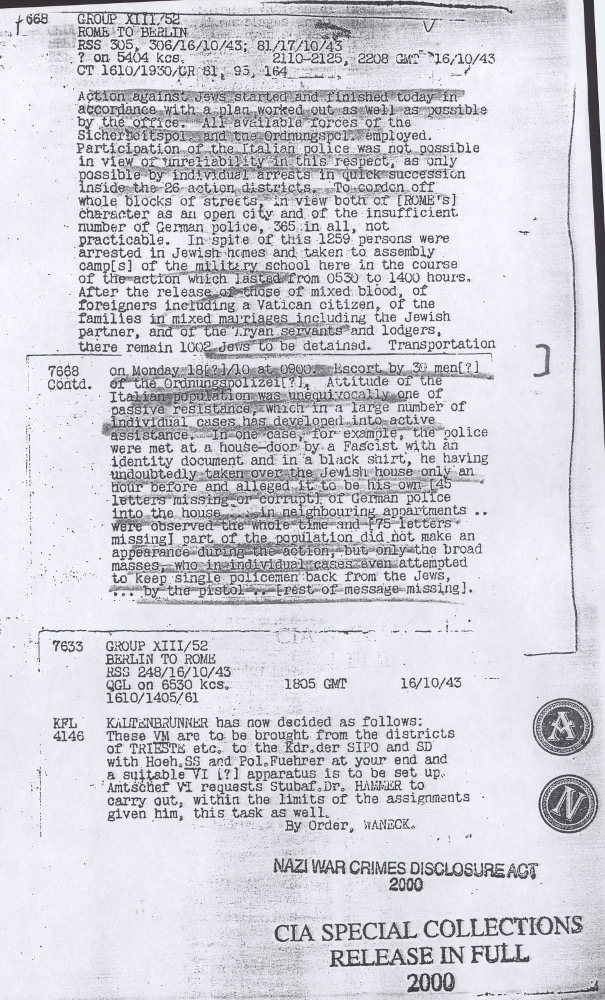

Beyond the front line, instead, the situation significantly deteriorated and the Germans began pursuing their goals to the detriment of the Jewish people. Immediately after the occupation of Rome, Heinrich Himmler commanded Herbert Kappler to “solve the Jewish question without delay in the territories recently occupied”, and a few days after the fall of Naples the Nazis started carrying out mass round-ups in the Roman Ghetto. It was the 16th October 1943. Of more than 1200 arrested, about 1000 were sent to Auschwitz right away. Only a woman and 15 men among them will come back.

In Kappler’s report we read that the plan was carried out “as well as possible”, an evidence of the speeding-up imposed by the events.

Kappler draws the attention to the fact that, in view both of the scarcity of means and also of Rome’s character as an “Open City”, it was not practicable to cordon off entire neighbourhoods and that operations were conducted mainly by German soldiers, because of the “unreliability” of the Italian police in this respect.

Kappler notes a general attitude of passive resistance of the Italian population, which developed in a number of cases into active assistance, as he writes.

Kappler’s words in the heat of the moment may also hide the explanation as to why the round-up in Rome let the Germans arrest “only” 1000 out of the over 7000 Jewish Roman citizens that lived there.

Città di Battipaglia

Città di Battipaglia