The Italian campaign. The events in the summer of 1943

Operation Husky

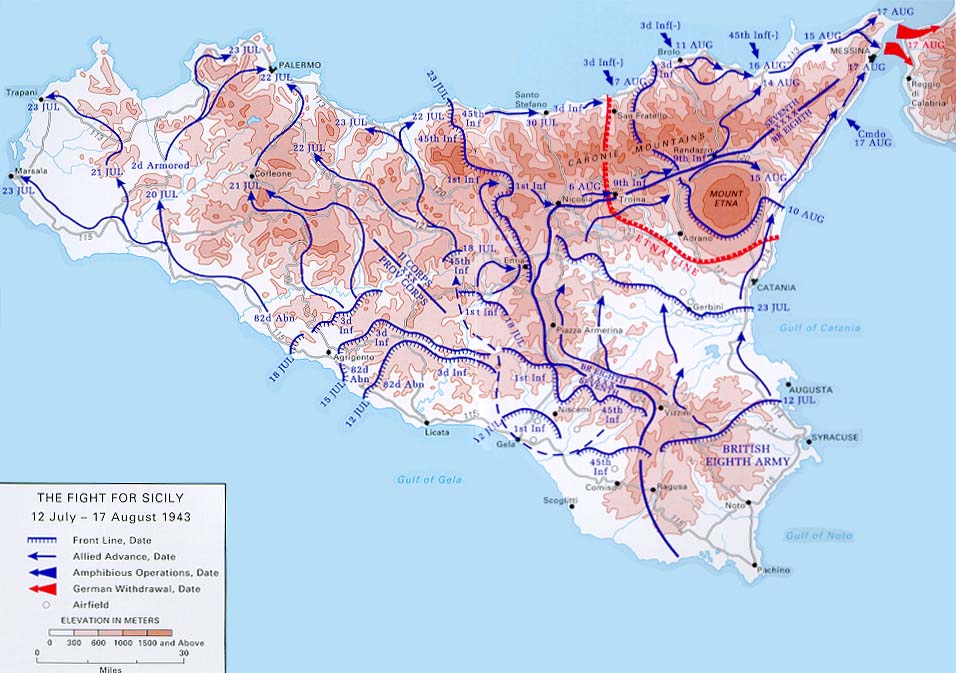

The first stopover of the Italian campaign was Sicily, a strategic and easily accessible point from Northern Africa, where the Allies had gained territory, thus forcing the Axis armed forces to withdraw. The landing took the codename of Operation Husky, which was launched on 10 July 1943, at sunrise. The two main Allied units were involved in it: the Seventh United States Army under command of General Patton and the British Eighth Army led by General Montgomery, both merged into the 15th Army Group under British General Alexander.

The operational plan after the landing included simultaneously the advance of the Seventh US Army towards Palermo to occupy the western side of the island, while the Eighth British Army was supposed to move towards the central eastern part up to Messina, performing in this way a pincer movement that would have surprised and trapped the Axis army.

From Messina to Cassibile: Italy surrenders to the Allies

Despite the fact that, from a military point of view, the operation failed to deliver the desired outcome, or rather, encircle the Italo-German troops, in actual fact the landing in Sicily influenced in a decisive way Italian public opinion and the country’s politic leaders.

Naval History and Heritage Command – Allied operations: General Bernard L. Montgomery and General George S. Patton Sicily

National Archives and Records Administration – Italy surrenders: gen. Geoffrey Keyes with gen.Giuseppe Molinero

Archivio Publifoto Intesa Sanpaolo – scenes of joy in Italy, Milan July 26 1943

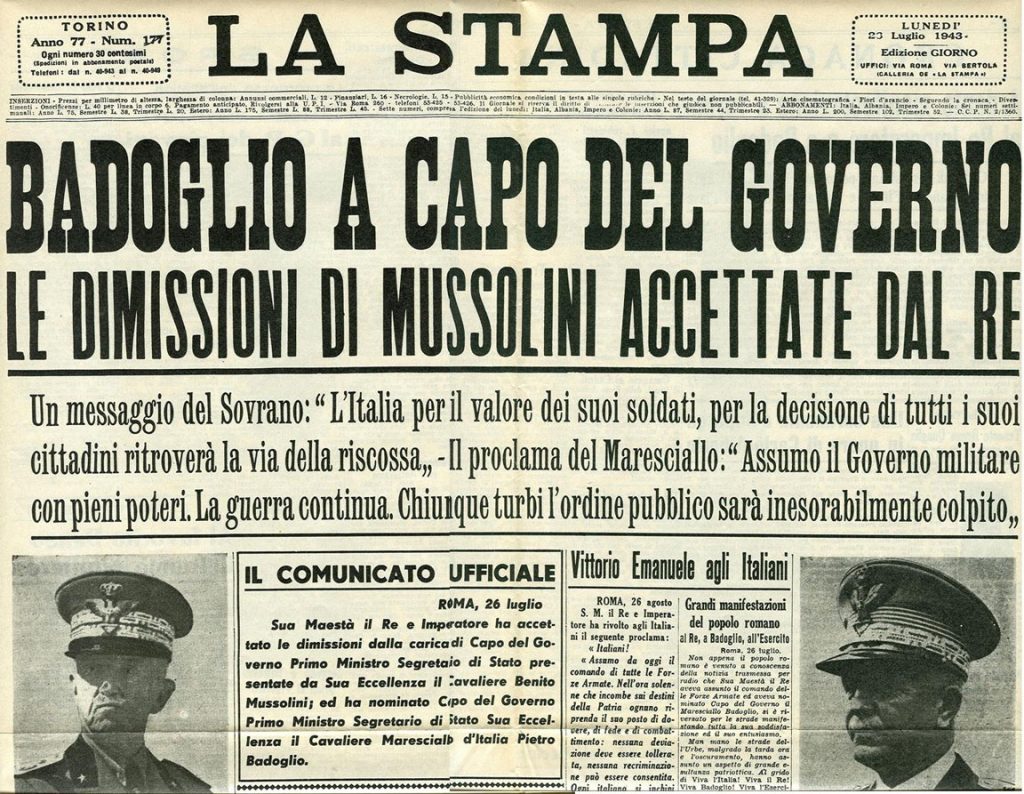

The presence of Allied troops on the national territory determined the fall of the fascist government and the signing of the armistice. After a little more than fifteen days since the Allied landing in Sicily, on 25 July 1943, Benito Mussolini was removed from office.

The task of forming a new government was entrusted by King Victor Emmanuel III to Marshal Pietro Badoglio, with orders to continue the war and maintain the alliance with Hitler.

The 51st (Highland) Division’s Farewell to Sicily

The brutality of the war doesn’t always have the ability to stop human creativity, which often appears as a tool to escape wartime daily life. Scottish Captain Henderson, in Linguaglossa, close to Catania, heard members of the 153rd Brigade, a part of the 51st Division, tuning up a bagpipe song, “Farewell to the Creeks”. Inspired by the music, Henderson wrote the lyrics to the piece that took the name of “The 51st (Highland) Division’s Farewell to Sicily“. Years later, Bob Dylan stated that he drew inspiration from that very song for his “The Times They Are a-Changin’” .

“Banks of Sicily (The 51st Highland Division’s Farewell To Sicily)” by Niall Townley

Operation Baytown

The Allies continued their military operations proceeding to advance towards all of Southern Italy, crossing Calabria and Puglia by means of two respective military actions.

On 3 September 1943 began the actual campaign of invasion of mainland Italy. In Reggio Calabria, under the name of “Operation Baytown”, landed the XIII Corps of the British Eighth Army and the 1st Canadian Division. Such an operation made it possible to obtain a bridgehead in the “toe” of the Italian “boot” and to bring other Corps troops closer to Salerno and Taranto, where following operations were planned.

On the same day, the 3 September 1943, the Badoglio Cabinet decided to definitively sign the armistice with the Allies, thus sanctioning the end of the alliance with the Axis powers and the subsequent transition on the side of two world powers, USA and UK. With a controversial decision, the signing of the armistice was kept secret and then revealed to the population and to the armed forces only on the following 8 September.

Hunt for the enemy: war is just around the corner!

Although Italy had acquired the ambiguous status of a “co-belligerant” with the Allies, the territory was occupied by the German Wehrmacht troops, that were ordered to neutralise Italian armed forces and to militarily occupy the peninsula. The Allied landing operations, therefore, became crucial to guarantee the withdrawal of the German troops and the liberation of the Italian cities from the enemy.

The Italian soldiers’ sacrifice

Every war brings with it its own inheritance of casualties, which converge in many impersonal statistics that try to piece together the inhumanity of the war events.

Even in the middle of such extreme events, certain episodes take on a stronger meaning in illustrating the war’s harshness. The 8th September represents a dramatic divide that describes, for opposite reasons, the irrationality of the fate that befell the soldiers involved.

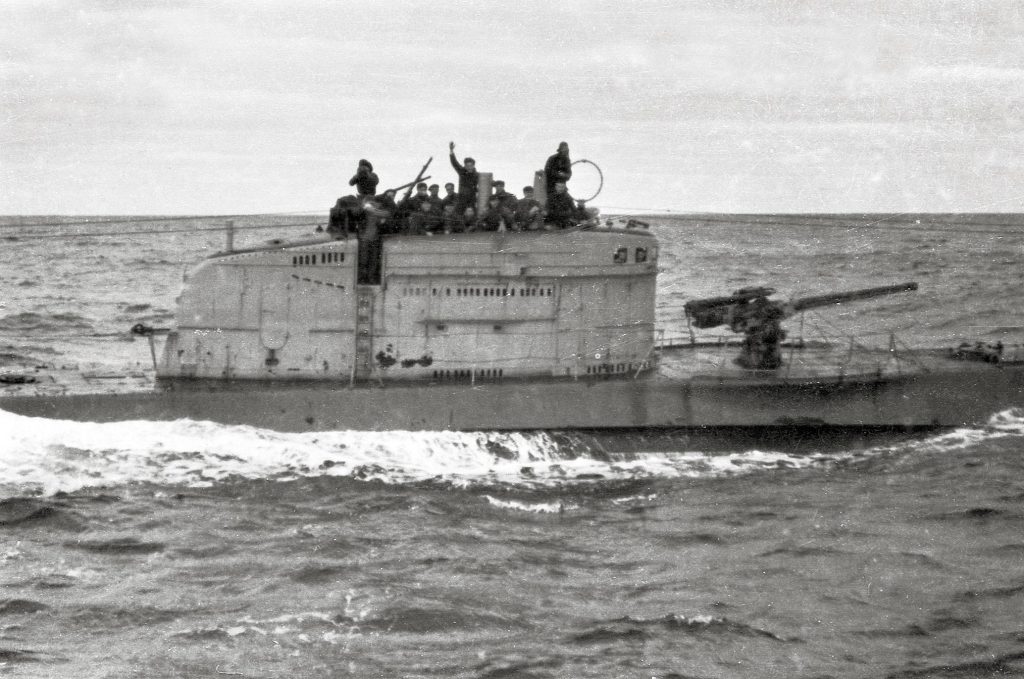

On 7 September 1943, when the armistice had already been signed a few days prior, the submarine Velella, under the command of Lieutenant Mario Patanè, was sent across the Mediterranean together with other submarines to perform actions of disturbance against the Allied fleet. It was spotted by the British submarine Shakespeare while it was surfacing, and then it was sunk. The 51 sailors that were on board still rest on the seabed offshore from Santa Maria di Castellabate.

Velella Saverio Cazzorla

Velella Mario Patanè

Velella Floris Cioni

Velella Giovanni Campito

Velella Eudechio Feleppa

Operation Slapstik

On 9 September 1943, with a simultaneous plan of invasion, the landing operations were launched in Taranto and Salerno. In Taranto the operation was coordinated by the I Airborne Division in collaboration with the Royal Navy in order to conquer the strategic harbours of Taranto and Brindisi.

The operation had been suggested by the Italian government, probably in anticipation of the king and the government’s displacement, which actually occurred in the early hours of the 9 September, in Brindisi, where the Italian army had taken over the territory. The ships of the Italian fleet left the port to surrender to the British in Malta and it was indicated to the British how to overcome the mined sections to enter the port.

The attack on Apulian ports and airports was also supposed to provide a diversion to avoid an excessive resistance on the part of the German forces in Salerno, but, in reality, whilst Kesselring arranged efficient defence plans, General Richard Heidrich in Puglia went for a strategic withdrawal whereby German troops restricted themselves to circumscribed battles to cover the retreat.

Città di Battipaglia

Città di Battipaglia