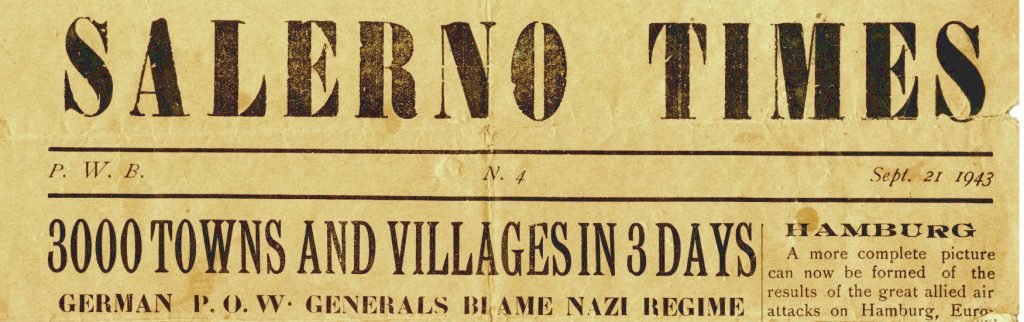

The Salerno landings, the risk of a new Dunkirk

Military strategy

One of the key stages of the Italian Campaign that was carried out by the Allied forces took the code name of “Operation Avalanche”. The occupation of the Salerno area was one of the main amphibious landings made throughout the Second World War, second in importance only to the “Operation Overlord” in Normandy. The region of Salerno was considered a strategic place to conquer Naples and its gulf.

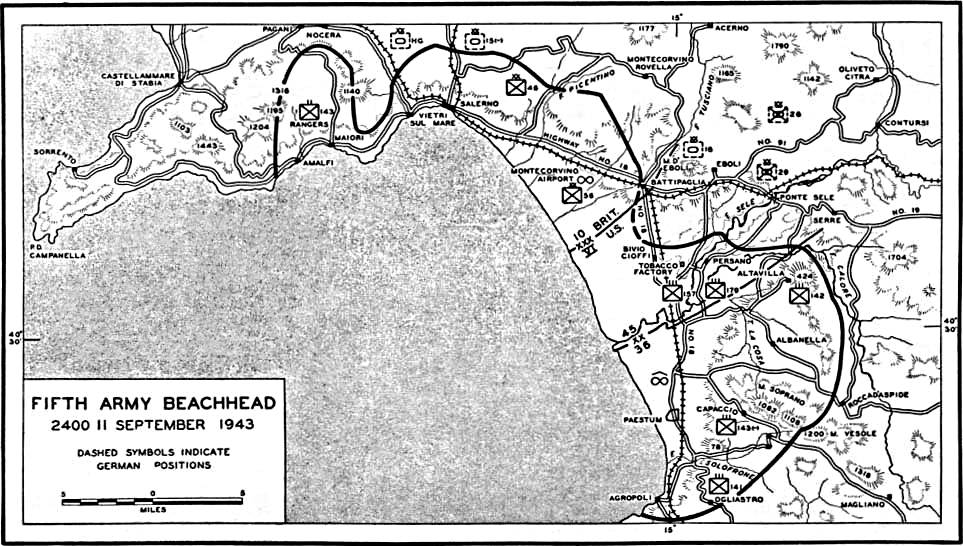

Operations were led by General Mark Clark, head of the Fifth Army, and by General Bernard Montgomery, head of the Eighth Army. The two Generals opted for a pincer movement, sharing the coastal area just behind the Sele river gorges. The beaches south of the Sele river were the responsibility of some divisions of the US Fifth Army, whereas the ones up north were up to the British army. The Americans’ objective was to advance towards the inland areas of the Sele, passing through Altavilla Silentina, while the British soldiers would have completed the pincer movement going from Battipaglia to Eboli, occupying the elevated hilly zones and thus gaining complete military control of the area.

Having completed the first manoeuvre, three US Army Rangers battalions would have landed at Maiori, firstly conquering the coastal zone and subsequently advancing towards the interior mountains from which it was easily possible to reach the Nocera-Pagani junction, that would have paved the way to the Naples plain. Meanwhile, the No 2 Commando of the British Army, along with the 41 (Royal Marine) Commando, would have landed in Vietri, with the aim to control the route of the state road SS 88, that links Salerno, Avellino and Benevento and which state road SS 18 Salerno-Cava de’ Tirreni intersects.

The Hampshire Lane

The Germans, nonetheless, didn’t get caught unprepared and organised a defence that made things difficult for the Eighth Army.

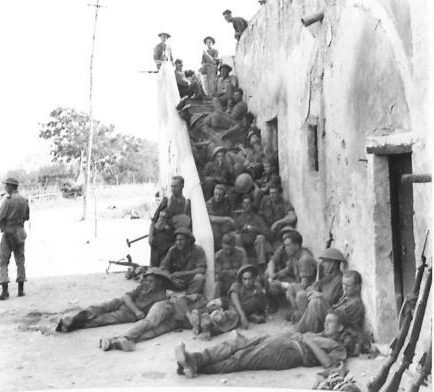

One of the most dramatic episodes for the British was the one which occured to the Royal Hampshire Regiment in a narrow little street leading from the beach to the Montecorvino airport, that was later named Hampshire Lane because of the incident.

Two companies of the Fifth Battalion were taken unawares by a German counter attack with tanks. The command of the battalion got trapped with many men between the walls of that narrow lane, lining it laterally. A tank moved forward opening fire, causing several deaths and injuries. By the end of day the Fifth Battalion had lost five officials, 35 soldiers and more than 300 men wounded and imprisoned.

The German resistance and the order to re-embark

The German defence had as a primary objective to retard the Allied action in order to protect the bulk of the troops marching from the south.

General Kesselring came up with a military strategy that, also thanks to the determination evinced by the German units, turned out to be so effective that it elicited a stubborn resistance and a sereis of counter attacks which forced the British to repeatedly fall back from important strategy objectives, such as Battipaglia.

The entire operation was on the verge of failing and General Clark gave orders to start preparing the troops re-embarkation plans.

What would have been the impact of the failure of “Avalanche” on the Italian campaign and the entire war?

The 51st (Highland) Division e the Salerno Mutiny

During the Salerno landings an extremely peculiar episode occured too: the largest mutiny in all of British military history (Salerno Mutiny).

The 51st Division had already fought in France and stood out during the African Campaign, taking part to the battle of El Alamein with heavy losses.

The Division also participated in the invasion of Sicily, after which many men were shipped back to Africa once more for health reasons. After recovery, 1500 of them agreed to go back to the front, but instead of being joined to the rest of their units they were taken to Salerno. There, 300 veterans refused to join other units.

Following General McCreery’s intervention, a few accepted to follow orders, but about 190 men stood firm on their positions. The accused were shipped to Algeria, sentenced to 12 years of forced labour, while the three sergeants promoters of the mutiny were sentenced to death. The sentences concerning the formers were eventually suspended, whilst the ones regarding the sergeants were subsequently commuted to detention.

Aerial and naval bombardments intensify

The success of “Avalanche” was eventually determined by the use of naval artillery and by air superiority. Besides employing the already occupied airports in Southern Italy, the Allies built several temporary airfields: by the Tusciano river, in contrada Serretelle and in Capaccio.

The Panzer Division attempted the last counter attacks particularly from Battipaglia, recaptured after the initial retreat.

The superiority of the Allied artillery determined the failure of the counter attacks, but, in the meantime, neither the towns of the Sele Plain nor those in the high grounds in close proximity were spared. Especially in Buccino and Altavilla, where General Clark suspected the Germans to be hidden in the villages, severe attacks were carried out. Battipaglia was likewise completely razed to the ground because of the bombings.

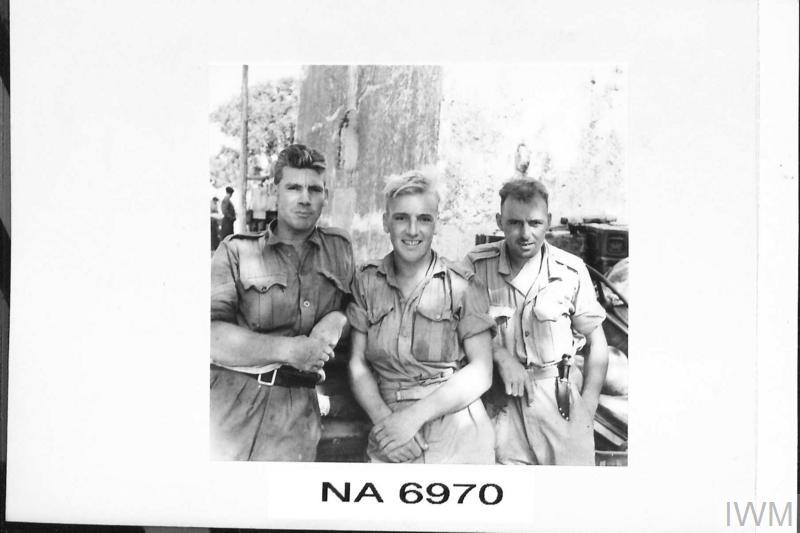

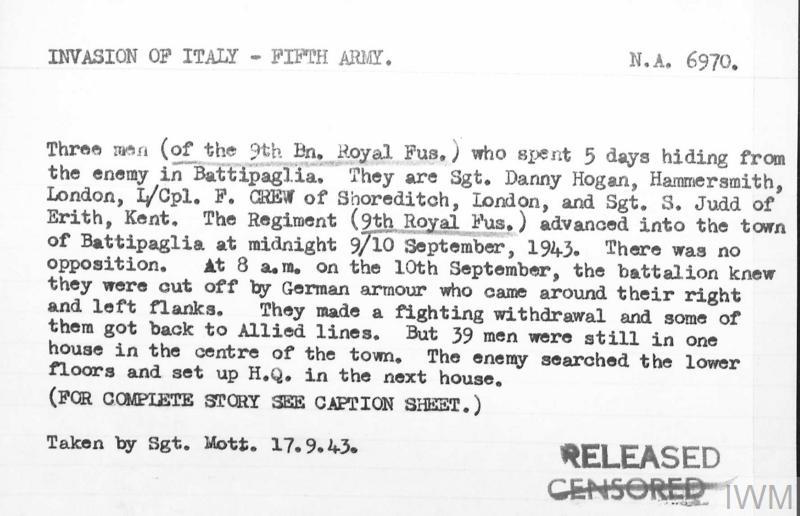

The story of Hogan, Crew and Judd

Three men of the 9th Battalion Royal Fusiliers were compelled to hide in Battipaglia for five days, trapped by the German counter attack: Sergeant Danny Hogan, Hammersmith, Lance Corporal F. Crew of Shoreditch, and Sergeant S. Judd of Erith. The 9th Royal Fusiliers advanced into the town of Battipaglia at midnight 9/10 September 1943. There was no opposition, but at 8 in the morning on the 10th September 1943, the Battalion was cut off by the German advance. 39 men stayed hidden in one house in the centre of the town. The enemy searched the lower floors and set up headquarters in the next house. The Fusiliers had no water and no food, they took turns to stand guard and prevent the others from snoring. On the fourth day Sergeant Hogan volunteered to find a way out. He reached the Fosso bridge and reported enemy positions in town. The bombers hit the town, still without chasing the Germans away, who searched the house in the days after and took 34 prisoners. Judd and Crew got to the second floor in the next house and hid there. An hour later they escaped, taking advantage of the cover offered by a further bombing.

The end of the battle of Salerno

Around the middle of September the outcome of the battle appeared to be more and more strongly in favour of the Allies and the Germans began to plan a retreat in safety towards more defensible positions.

Città di Battipaglia

Città di Battipaglia